Good morning, and welcome to Western Water Notes.

To get all my posts in your inbox, click the button to subscribe below. This newsletter is free, but if you find my work valuable and want to support it, please consider the monthly or yearly subscription plans below. You can also support my independent journalism by sharing these posts with friends or on social media. As always, drop me a line with feedback or suggestions.

Washington has long looked for ways to reform the General Mining Law of 1872, a 19th Century framework that still, 150 years later, controls how government agencies oversee mineral claims and permit new mines on lands that belong to all Americans.

For one, the law is often considered permissive to industry. At its core, the mining law “makes all valuable mineral deposits in lands belonging to the United States ... free and open to exploration and purchase…” And one of the top criticisms is that it gives companies (foreign and domestic) the ability to extract hardrock metals without paying any royalties to the taxpayers (the American people) who own them. This is in contrast to the royalties paid for coal, oil, gas and other forms of extraction. And in a recent report from the Biden administration (the latest White House to seek mining reform), an Interagency Working Group laid out other concerns with the mining law.

The report said the law fails to do the following:

“Direct mineral exploration and development towards areas that are appropriate for development and away from sensitive resources.”

“Promote timely development of mineral claims.”

“Promote early and meaningful engagement between mining interests, government agencies, and potentially impacted communities.”

“Provide the American taxpayer with any direct financial compensation for the value of hardrock minerals extracted from most publicly owned lands.”

The report was part of the Biden administration’s push to reform the law as federal agencies continue to use it as the framework for permitting mines to meet growing mineral demands from the energy transition. The Biden White House is not the first (and unlikely the last) to point out the flaws in the law. In the 1990s, Secretary of the Interior, Bruce Babbitt, declared his frustrations publicly. Babbitt was forced to hand over a mineral patent for 1,800 acres of public land in Nevada to Barrick Gold for just a little under $10,000, giving the Canadian company rights to gold worth an estimated $10 billion. Congress passed a law banning this practice in 1994. But the (lack of) fees and general structure of the Mining Law remain intact. An old law in modern times.

So is there any chance of reform right now? I wouldn’t bet on it.

But it’s still a question I’ve been thinking about as Congress takes up a different piece of legislation, the Mining Regulatory Clarity Act, which recently passed in the House.

First, a little more about the Interagency Working Group. Reforming the mining law has proven challenging, thanks to persistent, bipartisan pushback from congressional politicians in Western mining states (see: former Sen. Harry Reid). Reform efforts have been met with opposition from Democrats, which matters in a split Senate. In 2021, Reid’s successor, Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-Nev.), killed an effort to put a 4-8% royalty on hardrock mines in the “Build Back Better” infrastructure bill. The political calculus here: Don’t go against mining. And Cortez Masto won a second term in 2022.

With blocking mining law reform, all roads seem to go back to Nevada.

After Congress failed to include elements of mining reform in the infrastructure bill, the White House impanelled the Interagency Working Group in February 2022 to look at issues around reform. Despite a challenging political road to reform in Congress — including from Western Democrats — the Biden administration’s group released recommendations in 2023. It included, among other things, recommended royalties.

According to the Washington Post, then-deputy Interior Secretary Tommy Beaudreau told reporters in a press call that the legal status quo was proving “to be a recipe for local opposition, litigation and protracted permitting delays… I’m not saying we need to rewrite American’s mining laws every century, but maybe every other century.”

The National Mining Association came out against the recommendations, saying the suggested reforms would only slow down permitting. So did Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.). Cortez Masto and Sen. Jacky Rosen (D-Nev.) touted their opposition, standing up to the president for proposing rules “that would hurt Nevada’s mining industry.”

Which leads back to the Mining Regulatory Clarity Act. The law passed the House last month with nine Democrats voting in favor, and it heads to the Senate. The act would undo a 9th Circuit precedent in what is known as the Rosemont decision. In that case, an Arizona federal judge adopted a stricter interpretation of the mining law, affirmed by the 9th Circuit. Since then, it has been cited by other judges in the circuit, including in Nevada cases involving a proposed molybdenum mine and Thacker Pass.

The bill, introduced in the Senate by Cortez Masto and co-sponsor Sen. Jim Risch (R-Idaho), has bipartisan backing. InsideClimateNews’ Esther Frances, Megija Medne and Phillip Powell have a story about the legislation, and where the it is. Although Cortez Masto’s office said the bill would not fundamentally change the permitting process for mining on federal lands,” environmentalists remain very concerned. From the article:

In January, more than 90 environmental, climate and Indigenous groups sent a letter to Congress opposing the law and argued that the bill would allow mining companies to permanently occupy federal public lands without valid proof of mineral deposits and would preclude other types of development on federal lands.

“There cannot be a just and equitable transition to a carbon-free future, with legislation like this that sacrifices our lands, waters, public health, sacred sites and communities,” they wrote.

Or as Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D-Ariz.) called it, a “toxic mining free-for-all mess of a bill.” Grijalva, working with Western Democratic colleagues, has long pushed for reform.

The Biden administration came out against the bill (it said the administration already clarified the Rosemont ruling in a way that allows permitting to move forward).

But the big picture looks like this: Instead of getting its reform recommendations through Congress this year, the administration is watching a law heading to its desk that mining watchdogs say could make the 1872 act more permissive to industry.

That this is the dynamic after so many reform efforts seems telling.

The administration seems to hint at this. In their policy statement, they said the bill “threatens to undermine important clean energy and conservation goals, and detracts from efforts for comprehensive reform. The administration strongly opposes this bill.”

This is not really a story about the Biden administration though. Every Democratic administration over the past two decades has looked at ways of reforming the law — with little success. Why? I found this old interview Reid did back in 2018 very telling.

“Everyone knew nothing would happen,” Reid told NPR at the time. “Doesn’t matter. I was there and they couldn’t change the law. Unless I agreed. And I wouldn’t agree.”

Even with Reid gone, there remain enough bipartisan “no” votes to thwart reform.

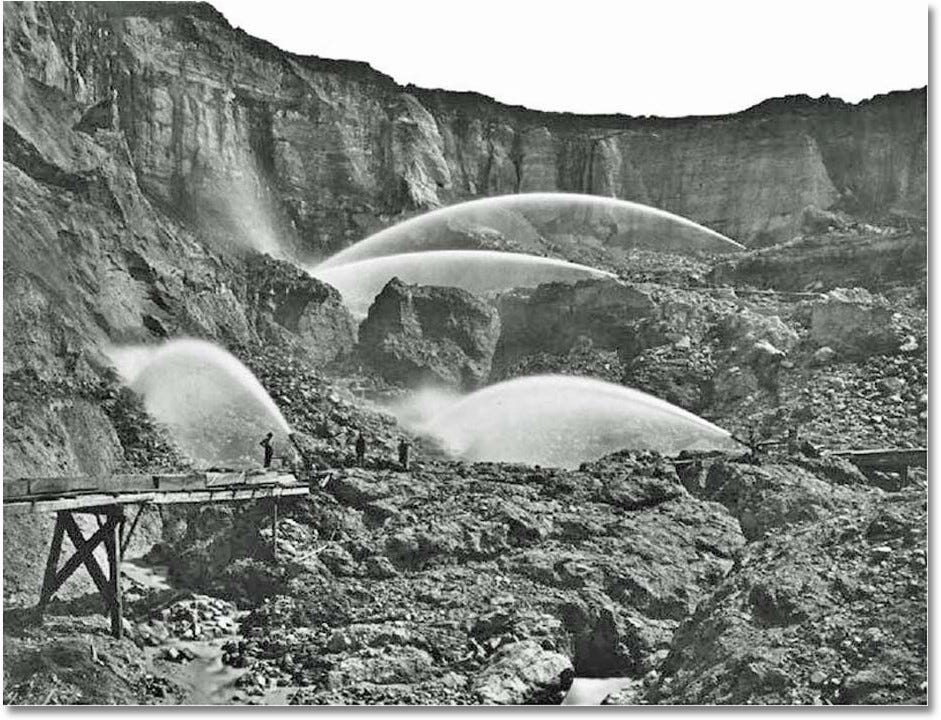

What does this all have to do with water? Fair question. But as more mines come online, I think it’s important to note that water use is tied to mining in more ways than one. Mines require water rights to move water, in addition to consuming water in other processes. The open pit in the first photo goes below the groundwater table. In order to access ore, the mine must pump groundwater, or dewater, the pit. Moving water in this way can have numerous cascading impacts, not only on the groundwater table but also on surface water sources, such as nearby springs, wetlands and streams.

It’s also worth noting that when it comes to water, there are numerous other federal and state laws layered onto the General Mining Law of 1872 framework. Modeling of how water cycles through mines is scrutinized in environmental impact statements.

As always, more to come and more to write about.

-Daniel