Hello, and welcome to Western Water Notes.

Today, I’ve got a follow-up to my last post on misinformation and wildfires.

To get all my posts in your inbox, click the button to subscribe below. This newsletter is free, but if you find my work valuable and want to support it, please consider a monthly or yearly subscription plan. You can also support my writing by sharing these posts with friends or on social media. As always, drop me a line with feedback, ideas for posts, and suggestions.

Several years ago, I was camping at a hot springs in the middle of Nevada. It was the drought, and the Colorado River’s two big reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, were at record lows. The river was in the news, and people were talking about water.

A couple, alarmed at what they viewed as California water mismanagement, started talking about how shockingly low Lake Mead was, and shared that they’d recently read about how California opened a straw at the bottom of the reservoir and was quietly stealing the Colorado River. Oh no, I thought. That’s not how it works.

We offered up fact-based information about allocations and contracts, accounting and water crediting, but they were totally convinced. And honestly, who can blame them?

When people start talking about how water works, they can look a little like this:

There’s no straw at the bottom of Lake Mead, at least not one belonging to California. If California uses lots of Colorado River water, it’s because it secured the largest share of the river through legal agreements forged in the 1920s. An entire federal agency is involved in accounting how much water it orders and takes. California stores water in Mead but does not divert from it. Not to mention the state’s priority water rights. Or that the conflict stems from more systemic and historic problems: That there are more paper rights to use water than there is water, an issue that is worsened as the climate changes. Or that these issues are socially, economically, ecologically, and physically knotted up. It is so complex and layered that some call these issues wicked problems.

As a communicator, I think about this stuff a lot. The complexity of water — from the physical constraints of moving it to the byzantine legal infrastructure layered over it, from the generational use that ties it to communities to its essential value in its place of origin — make policies complex. This same complexity, coupled with the fact that many are psychologically distant from its use, creates a vacuum for misinformation.

Since the fires broke out in L.A., I’ve been thinking about it all the time. Water really is a perfect vector for misinformation. Everyone gets its inherent value and still many are physically distant from the systems that deliver water to the tap or the farm. Many of our water systems rest on a foundation of complex tradeoffs involving economics, rates, ecosystems, power, inequities and social values that are imperfect and easy to exploit in a disaster, when systems are under strain and people are wanting answers.

So I can understand why it’s easy to believe there is a straw beneath Lake Mead and why actors like Donald Trump claim you simply need to turn a “valve” to move water from the Pacific Northwest to L.A., as it’s faced devastating wildfires in recent weeks.

But “there is no valve.” With the help of state and federal officials, California moves water from north to south through the California-run State Water Project and federal Central Valley Project. In the case of the federal project — where Trump ordered the federal government to increase deliveries — the vast majority of that water goes to agriculture. There is not water coming from the Pacific Northwest and beyond (a/k/a Canada) — though not for lack of trying (decades ago, when water projects united both parties in the Southwest, there were expensive ideas to tap the Columbia River).

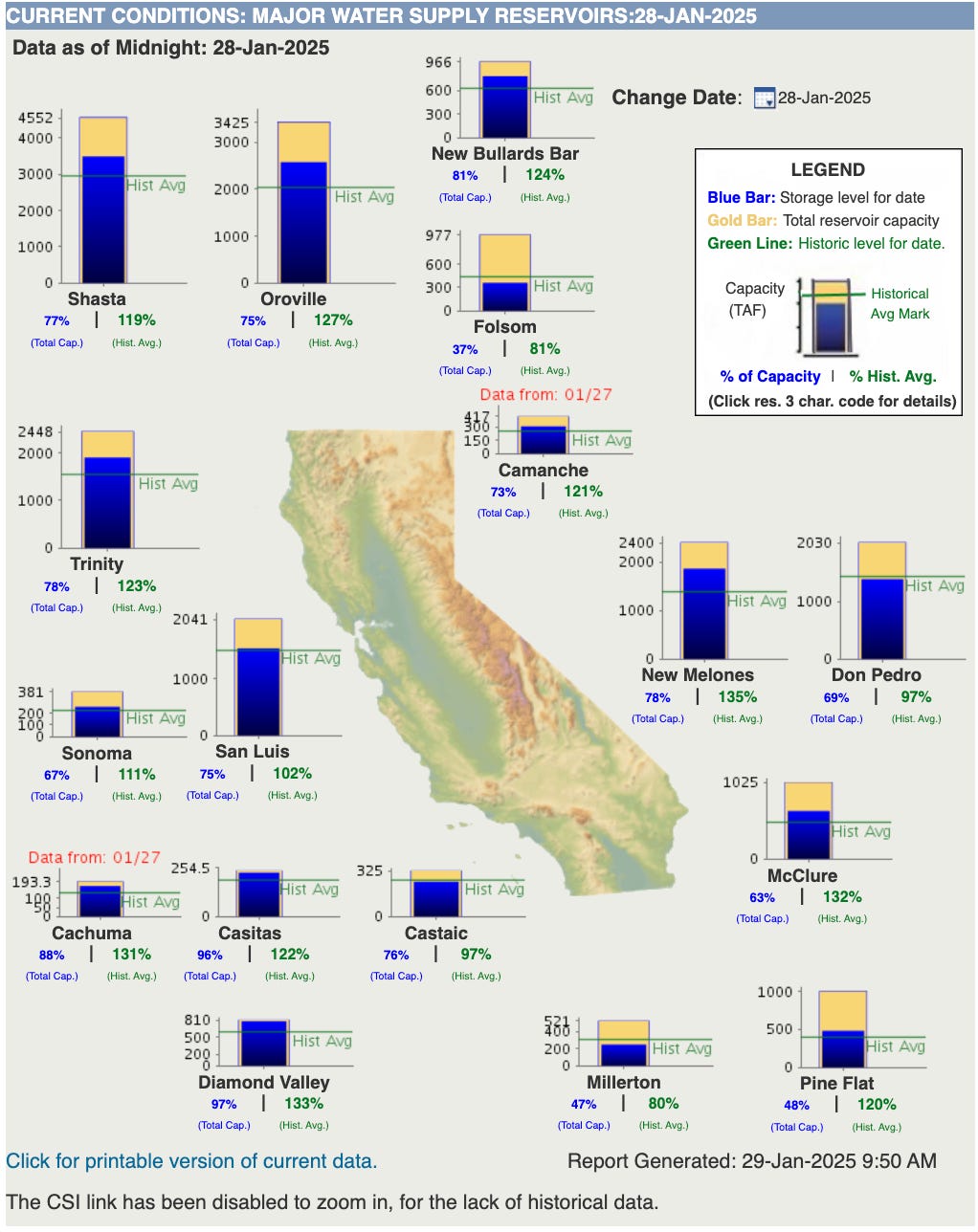

There was no military incursion into California this week to turn on the water, as Trump claimed. If more water is now on due to the president’s actions, as the press secretary declared, it’s because of scheduled maintenance, as state officials clarified. This is all not to mention that L.A. is at the end of the state-run water system (not the federal one), and Southern California reservoirs are mostly above average right now.

This is not to say there are not legitimate policy debates to be had about how water is managed as California diverts rivers from wetter northern California to drier southern California and the Central Valley. There are long-running disputes captured well in this L.A. Times story. But there are significant dangers about getting to outcomes in rhetoric that is wrapped around misinformation about how physical systems operate, falsely claiming that northern California diversions had to do with fighting the fires.

Misinformation has consequences, as Robert Greene writes for CalMatters:

Misidentifying the problem is like arresting the wrong person for serial murder or administering the wrong medication to treat a contagious disease. It provides the illusion that problems are being solved when, in fact, they are festering.

As many people have pointed out, how water gets from Point A to Point B is far more complex. Yet it’s not actually about any of that, anyway. The mis/disinformation about California water and wildfire is politics, more about sending water to large farms, not L.A., as Grist’s Jake Bittle writes in a piece about Trump’s executive orders on water:

…his attempt to relax water restrictions would move more water to large farms in the state’s sparsely populated Central Valley, a longtime pet issue for the president, who attempted a similar maneuver during his first term. This time he’s going further, proposing to gut endangered species rules and overrule state policy to deliver a win for the influential farmers who backed all three of his campaigns.

Between the rhetoric and the reality, there is a bitter irony here, too.

As a water expert with the Public Policy Institute of California notes, changing how the federal government operates its project may actually result in less water going to L.A. because of how California’s state-run water project and the federal-run Central Valley Project are tethered together in ensuring water quality standards in the Delta, where water is pumped south in accordance with rules to protect endangered species:

If the Central Valley Project were to “go it alone” and ignore state water rights and water quality laws, it may have significant unintended water supply consequences.

Assuming that Trump’s executive order directs the federal government to divert more water through the Central Valley Project, it “would likely lead to less water available for Southern California, not more, which I don’t think is the intention of the orders.”

That last point is to underscore how complicated things are on the ground, and why the rhetoric is far more complex than *valve on,* *new rules,* and *more water for all.*

Listening to Trump’s rhetoric reminded me of an experience I had reporting a story last year. I was writing about Idaho’s decision to curtail groundwater in the Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer. The state was seeking compliance with an agreement (one much litigated and debated) to cut groundwater use from one set of farmers to make another set of irrigators (who relied on the lower Snake River) whole. The reasons why rested on geology and the law, tied to a complex history stretching back more than a century — a period of time in which politicians reflexively encouraged development without dwelling on the consequences, not only to ecosystems but to existing communities.

What stood out to me was less that the state wanted to curtail water. It was how much misinformation was swirling around in a conflict that pitted farmer against farmer in counties that voted the same way by wide margins. A local irrigation district manager told me his field supervisor was answering calls about how the curtailment order was the result of Chinese collusion. There was a conspiracy about a faraway cobalt mine that was coming online in a completely different watershed. Soon came a slew of bad Google reviews for the district, even if what TikTok said was happening was actually not happening. They were stories, unrooted in reality, seeking to influence outcomes.

And in water, where usage agreements and compacts are often built on negotiation and diplomacy, such rhetoric can have some bearing on real-world policy outcomes.

When I listened again to my interview with the Idaho irrigation district manager a few days ago, his word choice was striking. He said the misinformation was like “a wildfire that’s run out of control.” And like fire, misinformation needs oxygen, an element that’s in abundant supply with how we get news in the attention economy.

Water systems, given their complexity, invisibility and inherent importance, seem to be especially vulnerable to the gap between rhetoric and material reality. One could imagine what happened in California easily happening elsewhere in the West, given the federal government’s role in managing dams and diversions, including along the Colorado River and in other basins, where governance is less an exercise of partisan reaction and far more polycentric, one of coalitions and networks, shifting alliances, values and priorities, ultimately responsive to the physics of precipitation and runoff.

It is, in part, why these lines stood out to me in a resignation letter yesterday from Anne Castle, the federal representative to the Upper Colorado River Commission:

The operation of the Colorado River is a complex web. Pulling on one thread of the web vibrates through the entire system, with significant potential for unexpected and adverse consequences. Sustainable operational solutions must be crafted by those who best understand and appreciate this complexity…

Edicts imposed from outside the Basin, such as recent proclamations concerning California water, based on an inadequate understanding of the plumbing and motivated by political retaliation, upend carefully crafted compromises, create winners and losers, and unnecessarily spawn the potential to adversely affect the lives of millions of people as well as the ecosystems on which they depend.

The full letter, posted on John Fleck’s Inkstain blog, is worth reading in its entirety.

As a reader said in response to my first post on this, misinformation is a disaster.

A few other things to watch:

In 2014, California passed its landmark Sustainable Groundwater Management Act after decades of aquifer overuse had led to land subsidence and dry community wells. Ten years later, the economic consequences of restrictions on groundwater use have come with significant economic costs for small and medium-scale growers. Important reporting in the Mercury News looking at the personal toll and the realities of SGMA.

New Mexico legislators are looking at bills aimed to protect intermittent streams in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Clean Water Act decision in Sackett v. EPA. The court, which constrained the federal law’s jurisdiction to “relatively permanent” created a potential regulatory gap in arid southwestern states, where a vast majority of mapped streams are considered to be ephemeral or intermittent. More form SourceNM.

The future of Colorado River funding, from KUNC.

Arizona’s governor announced a $60.3 million investment in water (AZPM)

After a dry January, a winter storm is on the way (San Francisco Chronicle)

The California Farm Bureau pushes back on dairy waste discharge rule (AgAlert)

A lithium project at the Salton Sea moves forward, the Desert Sun reports.

Can you explain the water run off to the Pacific Ocean and why it is allowed?