There is a reason so much nonfiction storytelling on water in the West begins with an aerial view of the landscape. When you see watersheds in shades of brown — with the occasional small blue river cutting through — scarcity and aridity feel far more real.

Limits on water are the reality in the West.

This newsletter takes a look at those limits in the Colorado River, which supports 40 million people in the Southwest. How water is used, moved, and managed in the Colorado River Basin is dictated by a series of interwoven compacts, treaties, laws, and court cases that collectively compose what is known as the “Law of the River.”

At the center of this legal manual is the Colorado River Compact of 1922.

That agreement divided the river between an Upper Basin (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming) and a Lower Basin (Arizona, California, and Nevada). The Upper Basin had to send a certain amount of water to the Lower Basin. Each basin got an equal slice of the river: 7.5 million acre-feet. But these shares were based on faulty assumptions about supply; They assumed the river’s volume was larger than it was.

Over the past two decades, the states have been forced to reconcile these assumptions (what was promised by the compact) with the reality that the river that a) the water was not there, and b) the river has shrunk in an increasingly hotter and drier climate.

This is more pressing now because the rules for how water moves through the river’s infrastructure expire in 2026. The federal government has given the states a deadline of November to come up with a draft of something new. Here’s some of what’s at play:

A bad water year

First, the supply backdrop.

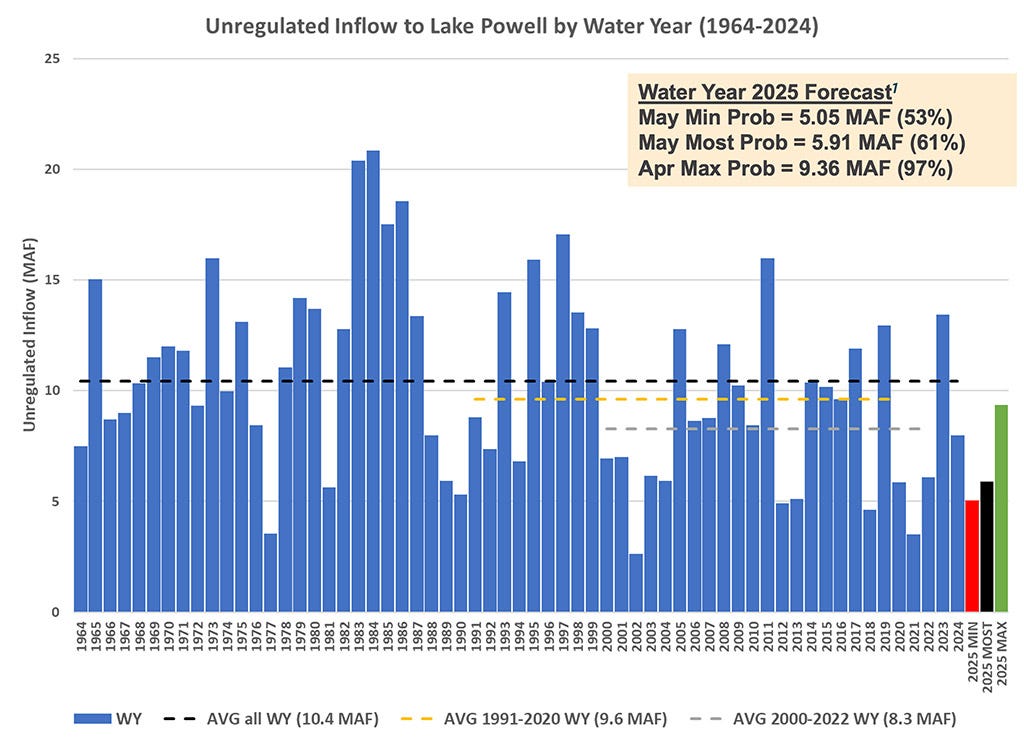

We humans like to believe we are the ones in charge, but it’s important to keep in mind what we cannot control: the water cycle. Since the early 2000s, Colorado River inflows into Lake Powell (the large storage reservoir in the Upper Basin) have been recorded at 8.3 million-acre-feet, far lower than the 20th-century average.

This year is on track to fall well below that average. It is going to be a dry year (as you can see below), on par with some of the lowest inflow years in the past two decades. The inflow forecast for Lake Powell for this hydrologic year is about 54% of average.

That is not good news for Powell, Lake Mead downstream, or the amount of water that remains to hold over for dry years. Reservoir storage is already historically low. And Colorado River reservoir storage will gain only a fraction of the volume of water it has in past years, as a post by Utah State University professor Jack Schmidt explains.

Climate scientists have warned for years that as temperatures increase, the Colorado River’s streamflows will decrease. It’s happening now. As of April 1, snowpack in the Upper Colorado Basin was 89% of average, not far from the norm. That divergence between near-average snowpack and below-average runoff is “stunning,” to borrow a term that Colorado State University’s Brad Udall used in an interview with Politico:

I use the term, “beyond awful.” This year we had pretty good snowpack, almost 95 percent of normal snowpack, and we’re going to get 45 percent of normal runoff out of that snowpack, which is stunning.

…What’s been disturbing in the basin is we have seen modest precipitation declines, especially in summertime, that seemed to translate into large reductions in flow the following year because of reduced soil moisture that serves as a buffer from one year to the next. Basically, if it’s dry in the summer, the soils dry out and the next spring, when the snow pack goes to melt, instead of that water flowing over land into rivers and creeks, as it did historically, it now goes to recharging the decimated soil moisture from the previous year.

Shifting to a supply approach

The news that made recent headlines was that negotiators for the seven basin states, after months (years?) of public and private infighting, might be reaching a consensus solution for how to manage the river going forward. Some are calling it a “divorce” or, in kinder lingo, a “conscious uncoupling.” Aspen Journalism has a good article on this.

As things currently stand, the operating rules for the Colorado River tie releases from Lake Powell to how much water is in Lake Mead, the reservoir from which Arizona, California, and Nevada pull water. The rules are complex and headache-inducing, full of loopholes that can be gamed, and they are tethered to the hydrological assumptions that are not reality. That is, they are divorced from supply. For all of those reasons, the rules have proven to be a source of tension between the Upper Basin and Lower Basin.

The proposed alternative represents a shift. Instead of the current scheme, the plan would tie how much water is released from Lake Powell to the estimated supply, or the “natural flows,” of the river. In other words, the Upper Basin’s release of water to the Lower Basin would hinge on water supply, how much water is actually in the river.

That makes… sense.

The supply-based approach seems intuitive, logical, and you might wonder why it’s not already been done. The details and the legal framework present a trickier picture.

Under this plan, the Upper Basin would deliver a percentage of water downstream to Lake Mead based on the three-year rolling average of Lake Powell inflows. What that percentage looks like is a major sticking point. 50-50? A top Arizona water official already said his state won’t go for that. And what are the bounds of the deal? What is the maximum or minimum amount of water that could be released without affecting things like power production or dam operations, or (optimistically) flood control?

If you do get some agreement around questions like that, the idea is that both basins would manage their affairs based on existing supply, rather than a number from 1922.

Upstream of Lake Powell, the Upper Basin would have to implement conservation to ensure that the required amount flows downstream of Lake Powell. The Lower Basin, which has already agreed to more cuts, would have to find more ways to use less, too.

There’s a good post on all this from Jonathan Thompson’s Land Desk Substack this morning, breaking down the proposal in accessible terms with some excellent charts.

I’d read about the plan in various news outlets, but my curiosity needed to hear it all firsthand… so I listened to a presentation on the plan at the Arizona Reconsultation Committee for more details. I came away thinking this: A divorce? I’m not so sure.

Call it what you want, but it seems that the two basins would still have a significant relationship with one another. Their fates are intertwined in many ways, and Arizona water officials noted that “natural flow” supply-driven rules would need to honor the “Law of the River,” premised on the two basins’ compact requirements to one another.

The interpretation of that “Law of the River” and more specifically the compact still seems like it would be important in deciding on percentages for Lake Powell releases.

Measurements matter

One other thing: What are the river’s “natural flows?”

It’s harder to know what a river’s natural flow is than you might think. “Natural flow” is a hydrologic term that describes a river’s streamflow without human alterations (think dams, diversions, irrigation, etc…). Because we have altered so many rivers and streams, it becomes a big math problem — accounting for what would be in the river minus water lost through diversions, seepage, and crop evapotranspiration.

It is an estimated value, meaning that different scientists and water managers debate about how to calculate it with accuracy. Currently, federal water managers with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation calculate natural flows on the Colorado River, first by releasing a provisional estimate and then updating after several years. Yes, years. That’s a long time to wait when you are making real-time management decisions.

Federal, state, and university scientists collect valuable data to inform natural flow calculations, and they would be fundamental to a supply-driven river management structure, which seems to need a reliable and established method for calculating complicated variables (i.e., evapotranspiration) that go into natural flow equations.

E&E News took a look at this in more depth.

Pushing Cadiz

At the Arizona Reconsultation Committee, Scott Cameron, the Interior Department’s acting assistant secretary for water and science, spoke to the room, mainly voicing the federal government’s goal to get the seven basin states to reach a negotiated deal.

He said similar things to what assistant secretaries have said in the past, laying out how Interior could intervene on the Colorado River through federal authority as the water master in the Lower Basin and a reservoir operator in the Upper Basin. He also encouraged irrigated agriculture, with priority rights, to “be part of a solution” before junior water users (typically cities, municipal, and industrial users) face a crisis.

Then he said something I hadn’t heard before about augmentation in a state that is facing tremendous pressure to find alternative supplies to the Colorado River in a region where most available water is spoken for. He floated, as one alternative, the Cadiz groundwater project in California’s Mojave Desert.

Here’s what Cameron said to the committee of Arizona water leaders:

Are you interested in exploring what changes in law, regulation, policy, or simply old habits need to be changed to transfer, lease, or exchange water across state lines? For instance, the San Diego County Water Authority now has excess water due to a successful [desalination] program and conservation. They want to put that water to good use somewhere. Would Arizona be interested in that water?

Similarly, Interior is going to execute a memorandum agreement with the proponents of the Cadiz project in Southern California, but Cadiz sponsors think they have a lot of groundwater that could go somewhere. If it turns out they are right, would Arizona want to have a conversation about that water?

Developers have long sought to pump groundwater from the Mojave Desert and sell it to Southern California (perhaps now Arizona?). The controversial project has faced its share of political opposition over the decades, and environmentalists say it’d decimate sensitive desert ecosystems. The project has never managed to get buy-in from the big player: the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. Politico has more on it.

Lots more to say about this. Filing it away for a future newsletter.

Seniority rules?

One other thing Cameron said that caught my attention, more an acknowledgment of a reality facing the federal government than anything else. A remark about priority and the “first in time, first in right” rules used to manage water in the West:

“About 80% of Arizona's population is served by the Central Arizona Project, but the CAP and its customers generally don't have senior water rights. Having senior water rights is a wonderful thing, but having senior water rights does not give you a free pass to ignore what's happening in the greater community.”

Again, filing away for a future newsletter.

A few other things:

Tailings pond may be leaking into the Great Salt Lake (Salt Lake Tribune)

Report looks at just land transitions in California (Union of Concerned Scientists)

After years of work done by our community of practice and scientists, we just published a much needed and comprehensive framework for best practices in cropland repurposing that can benefit everyone involved. This community of practice includes community leaders, farmer and farmworker advocates, scientists, and practitioners across California’s agricultural regions.

How does cloud seeding work in the Mountain West? (KUNC)

Can California stop the spread of golden mussels? (CalMatters)

More data centers. More water use. More on this in a future newsletter.

This article really hit home for me when the phrase ‘quality of data’ matters. I can tell you most truthfully that the process of collecting raw hydrological data is not cheap, nor once a collection is started at a site it is not a ‘set and forget process’. Sensors at a site normally require monthly calibrations and stage discharge measurements also being done on a schedule. Overall, it’s not a cheap process.

You mentioned a site count. I’m assuming that this references sites in the upper basin only. The majority of them being USGS and maybe several at Reclamation Dams.

As a person who once supported a hydrologic data collection system, I would be asking about the instrumentation used at these sites? I know the accuracy at the Dams and the accuracy you would get at a typical gage.

I’ll also mention that there will always be some errors in the data. No data that I’ve been involved with had some margin of error in the collection. The concept of absolute data doesn’t actually exist.

Bringing this concept into the big picture when looking at several different sources when making that decision about how the water flows. You can see that assuming all sources to be correct can cause uncertainty.

I can tell you this, the more detailed data you can collect actually opens your eyes to the dynamics in play. The flip side to this is it takes more time to digest this information.

I only wish that there is more support to the data collection effort on the river.

Also it was mentioned about growing Alfalfa. Farmers typically get 12 cuttings per year in the Lower Colorado Region. It’s the perfect crop. Low maintenance compared to other crops. Almost like mowing the lawn. Think of it. Bringing in a harvest each month from the same field.

When asked about Alfalfa production, the Farmer says - “You like Dairy Products…Right?” I’ve been in my share of irrigation districts from Bullhead City to Yuma in the river valleys and haven’t seen any significant Dairy production in that area. For that, go to California’s Central Valley.

Parting thought. It takes 1850 gallons of water to produce one pound of beef. Most of which being Alfalfa.

The simplest solution to the SW water problem is to stop growing hay and alfalfa, cattle feed under the blistering summer sun in the Colorado, Imperial, and San Joaquin Valleys. Production could be moved to vast Midwest acreage devoted to corn ethanol crops, which really are pretty lame, especially with the fracking largesse.