Hello, and welcome to Western Water Notes. Thanks as always for following, and thanks to my new subscribers! Been a busy month so far, but I’m hoping to pick up the pace again here soon—even if to resurface for some shorter dispatches. As always, please don’t hesitate to reach out with ideas or feedback. Wishing everyone a good weekend, Daniel

At a time when civic life seems to be shrinking inward, I have been drawn further into the past to understand the present—in water and all things. We are living, breathing people and communities only because we stand upon all that has passed.

Nonfiction writing, at its core, is like putting together a puzzle that fuses time, space and place. It is piecing together the world to find out who, what, where, when, and why reality is the way that it is. And those questions necessarily hinge on the past.

To know today and tomorrow fully is to know yesterday. And in history, I’ve always found lessons and refuges, stories tragic and heroic, resilient and timely, spectacular and mundane—and plenty of stories in between. More gray areas than you can count.

This is true in so many types of history, both the personal and collective kinds. But as I’ve written here before, history feels especially pronounced in water, a substance so tied to place and time, governed in the West by a legal framework that prioritizes use on the basis of historical claims. Time and history weigh on all things, and they also shape the narratives and stories we tell each other.

It’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot these days. Who gets to write history, tell it, shape it, and memorialize it. Perhaps more importantly, what is the role of the past?

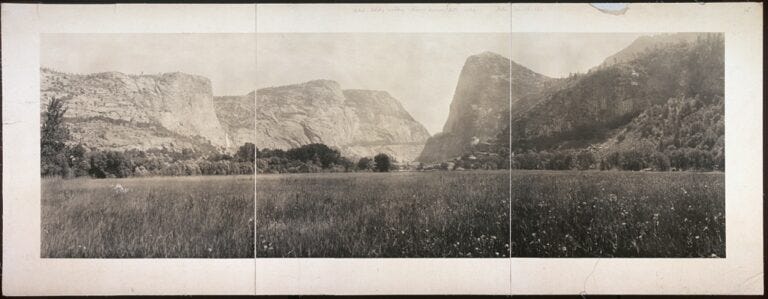

A few months ago, I visited the Pulgas Water Temple (pictured above) outside of San Francisco with a friend. The palatial temple (and believe me, it is) was built—in the words of the city’s Public Utilities Commission—“as a monument to the engineering marvel that brought Hetch Hetchy water more than 160 miles across California.”

This, of course, tells only one side of the story. The engineering marvel this temple celebrates was the damming of one temple to build another of a very different kind.

At the start of the 20th Century, as thirsty cities and the federal government turned to large-scale reclamation projects to reroute the West’s rivers, San Francisco embarked on building a diversion to import water by damming Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. To commemorate this diversion, the city erected the water temple.

But it is not the only temple here.

O’Shaugnessy Dam, which inundated Hetch Hetchy Valley, is a sort of temple in its own right, an articulation of the belief that engineering massive storage reservoirs could solve the West’s imbalance between supply and demand of water. It is not a coincidence that Mark Resiner’s Cadillac Desert uses temple to describe mega-dams.

He writes:

“When archaeologists from some other planet sift through the bleached bones of our civilization, they may well conclude that our temples were dams.”

For decades before the dam was completed in 1923, the question of whether to impound the Tuolumne River at Hetch Hetchy and within a national park was a contested issue that divided the public at the time. Hetch Hetchy was a sanctuary, and it is notable that temple is the same word that John Muir used to describe the valley.

In arguing against the dam, Muir said the following in 1912:

“Hetch Hetchy is a grand landscape garden, one of nature's rarest and most precious mountain temples. As in Yosemite, the sublime rocks of its walls seem to glow with life … These temple destroyers, devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for Nature, and, instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the mountains, lift them to the Almighty Dollar…

Of course, Muir’s use of the word “temple” comes with its own troubled history that travels back to the conservation’s exclusionary and racist roots during the Progressive Era. A temple for whom? A temple for the enjoyment of white people? The creation of Yosemite and national parks more broadly—to protect what Muir saw as his temples—ultimately led to dispossessing Indigenous communities of their ancestral homelands.

All of these “temples” belong to the past, and yet are still so present with us in ways that are often invisible. As I visited the Pulgas Water Temple, I became very aware of just how irrigated and green the lands were; Cypress trees line a large reflecting pool. It felt as constructed as the dam itself or the idea that nature is a temple owed to some but not others. The Pulgas Water Temple itself left no doubts about where the water came from, and that seemed to be the very point. "I give waters in the wilderness and rivers in the desert, to give drink to my people," the temple says, quoting Isaiah 43:20.

I think a lot about how these words, myths, and monuments seep into and continue to shape our understanding of water in the West today. The same “reclamation” ethos behind Hetch Hetchy was a driver in the legal framework that governs water; Water must be put to use, re-routed and “reclaimed” from its natural state. Despite its many successes in remaking the West, it was the same principle that led to the overuse and overallocation of rivers, so often excluding Indigenous communities and ecosystems.

Understanding this past, in all its complexity and language, is a way to move forward. In 1988, the Reagan administration declared the federal Reclamation Era of massive water projects largely over; It said “the arid West essentially has been reclaimed. The major rivers have been harnessed and facilities are in place or are being completed to meet the most pressing current water demands and those of the immediate future.”

It’s worth scrutinizing this more (more for a future post)…

But reclamation lives on in monuments and words, ideas and proposals, even as water managers work to reconcile a century of past decisions with the values of the present.

More water history to come, until then… some news:

Low streamflow on the Rio Grande

From my New Mexico Substack/journalism colleague and friend Laura Paskus:

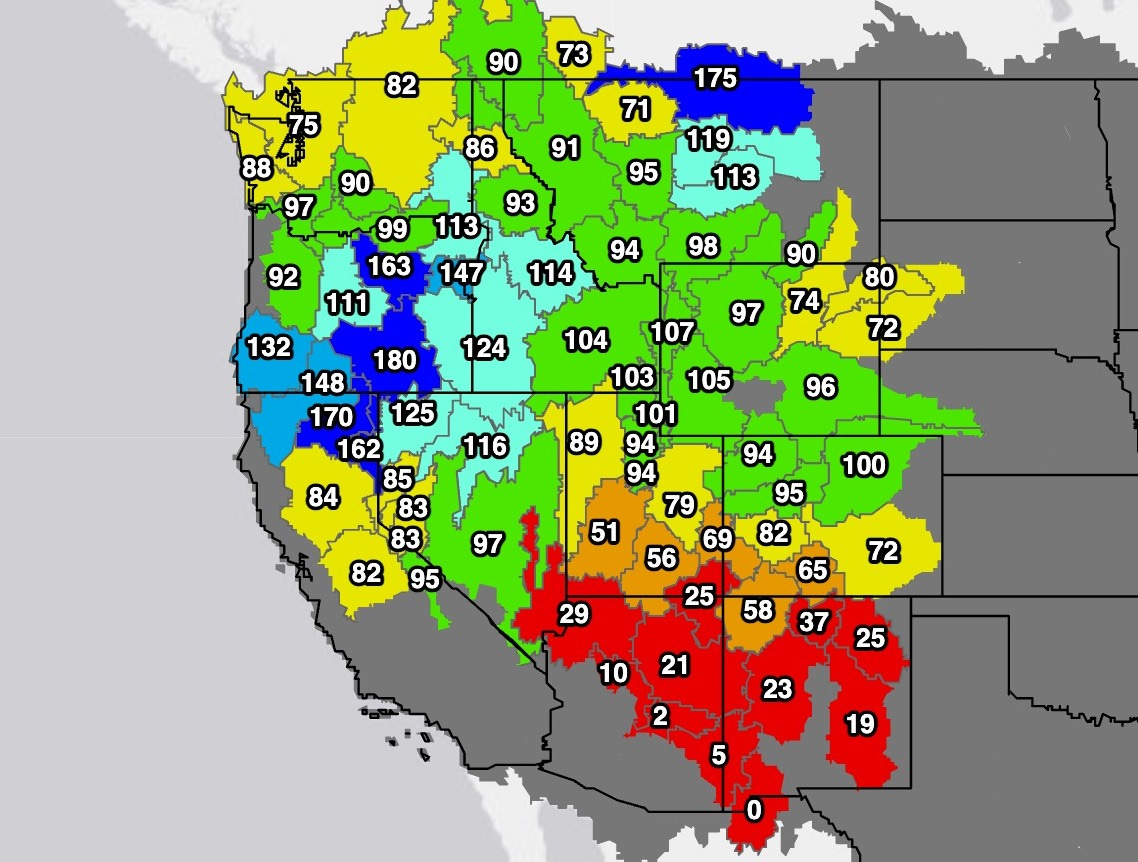

If you live in the Middle Rio Grande Valley, you’ll have noticed that the river is dropping. Fast.

Long sandbars are emerging in the Albuquerque stretch as the river shrinks, and already, flows are only 86 cubic feet per second in Bernardo. For perspective: On this day in 1985, the river there ran at 5,110 cfs. And over the last 42 years, the median flow on this day was 796 cfs.

Upstream, in Albuquerque, the Rio Grande is running at 300 cfs. (Over the last 52 years, the median daily flow was 1,340 cfs.)

Already, irrigation supplies are constrained, and as I’ve already written this spring, there isn’t much water stored in upstream reservoirs. That also means there isn’t water in upstream reservoirs for the river itself — and the creatures who rely on the waters.

To understand more about what’s happening, you can look at all the USGS stream gauges and read the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s April 1 New Mexico Water Supply Outlook Report.

Buying back groundwater rights in Nevada

A good story from The Nevada Independent’s Amy Alonzo on legislative proposals to buy back groundwater rights in places where there is not enough water to go around.

“Farmers and ranchers … across the political spectrum recognize that water is moving differently on the landscape than it did even 10 years ago,” said Peter Stanton, executive director of the Walker Basin Conservancy.

Closing out my tabs:

The Tijuana River is ranked the second most endangered (L.A. Times)

Opinion: DOGE quashes a Klamath Basin comeback (Seattle Times)

California commercial salmon season is shut down—again (CalMatters)

Can “toilet to tap” save the Colorado River? (Land Desk)

The origins of water on Earth, revisited (phys.org)

Why a Nevada water utility is watching tariffs and construction (Review-Journal)

My...How I enjoyed reading this. You summed it up nicely. There is something spiritual about the river. My own experiences of having been working on the Colorado River for two and a half decades on a daily basis, you get to see how personal it all is. Your comments about Dams and the infrastructure was spot on as well.

You mention about Temples. Most people are not aware that in ancient Egypt that the high priests measured the river levels with a structure called a Nilometer. Todays equivalent being a stilling well at a Dam or Stream Gage (we call them Gages, not Gauges in the trade). In some cases Nilometers were part of a Temple. I always thought that it was ironic that my own job of measuring the river was handled by the elite in earlier times but understand the spirituality aspect of it.

I'll give you an example. The Stilling Well that measures Lake Mead at Hoover Dam can be compared to the Nilometer in several ways. The Nilometer was used to predict how well the upcoming growing season would be by the number of Cubits measuring the depth of the Nile before it traversed into the Delta. If the reading was low, bad times ahead. Same with the Lake Mead Stilling Well. The Lake Mead Stilling Well is an interesting place which few have seen. It resides in the center of the Dam. It straddles the Nevada/Arizona state border and physically is in two different time zones. You access it through a tunnel in the Dam (we call them Galleries) and you have to walk up a set of concrete stairs to enter it. You actually get the feeling that you're ascending to an Alter. It's an eerie place as you can peer down the well into nothingness due to the lower levels of the lake, You also hear voices in the background while there. It's not the whispers of those ancient Egyptian Priests nor the moans of the unfortunate workers encased in the concrete (another myth) but the ramblings of tourists a few feet above echoing down a drain pipe.

Just another day working on the river. It was noble work...