Hello, and welcome to Western Water Notes.

To get all my posts in your inbox, click the button to subscribe below. This newsletter is free, but if you find my work valuable and want to support it, please consider the monthly or yearly subscription plans. You can also support my independent writing by sharing these posts with friends or on social media. As always, drop me a line with feedback or suggestions.

Watching the annual Colorado River gathering in Las Vegas this year felt a bit too much like sitting in a courtroom listening to two opposing parties plead their cases.

Talks over sharing the shrinking river are getting more adversarial.

Each year at the conference, representatives for the seven U.S. states that divert from the Colorado River deliver to the attendees (a broad constituency of water users — tribal governments, irrigation districts, cities, environmentalists) an update on how they are negotiating sharing agreements in a river that supports 40 million people.

Last year, the seven principal negotiators appeared on the same panel. They spoke to, or at least with, each other. But this year, the seven-state panel was split in two along the fractious lines carved by the river’s geography. The first panel featured the three states in the Colorado River’s Lower Basin — where a majority of the water is used — and the second featured four in the Upper Basin — home to the river’s headwaters.

The leaders in the two basins spoke at and past each other, seeming to preview their arguments over the history and meaning of a deal (the 1922 Colorado River Compact) more the 100 years old. Soon, it was revealed to the audience that, despite being in the same city for days, the negotiators had not met together in person, as is customary.

The “..speakers invoked Dr. Strangelove, the Hunger Games and Alice in Wonderland to convey the dire, darkly dystopian and illusory state of the negotiations for how the Colorado River will be shared in the future,” wrote Aspen Journalism’s Heather Sackett.

Yikes.

“We really need to understand that the enemy we’re battling right now is not the Upper Basin. It’s not the Lower Basin: it’s hydrology,” said Brandon Gebhart, the negotiator Wyoming, as the Colorado Sun reported last week. “All the rhetoric, the saber rattling and other distractions going on right now are bullshit. It needs to stop.”

Yikes. Because the stakes are high. The seven states are (as they have been now for several years) trying to reach consensus on a new set of shortage rules to replace the river’s current operating guidelines set to expire in 2026. And the clock is ticking.

Seeing is believing

Underneath all of this conflict (and driving it) is a river that is getting smaller.

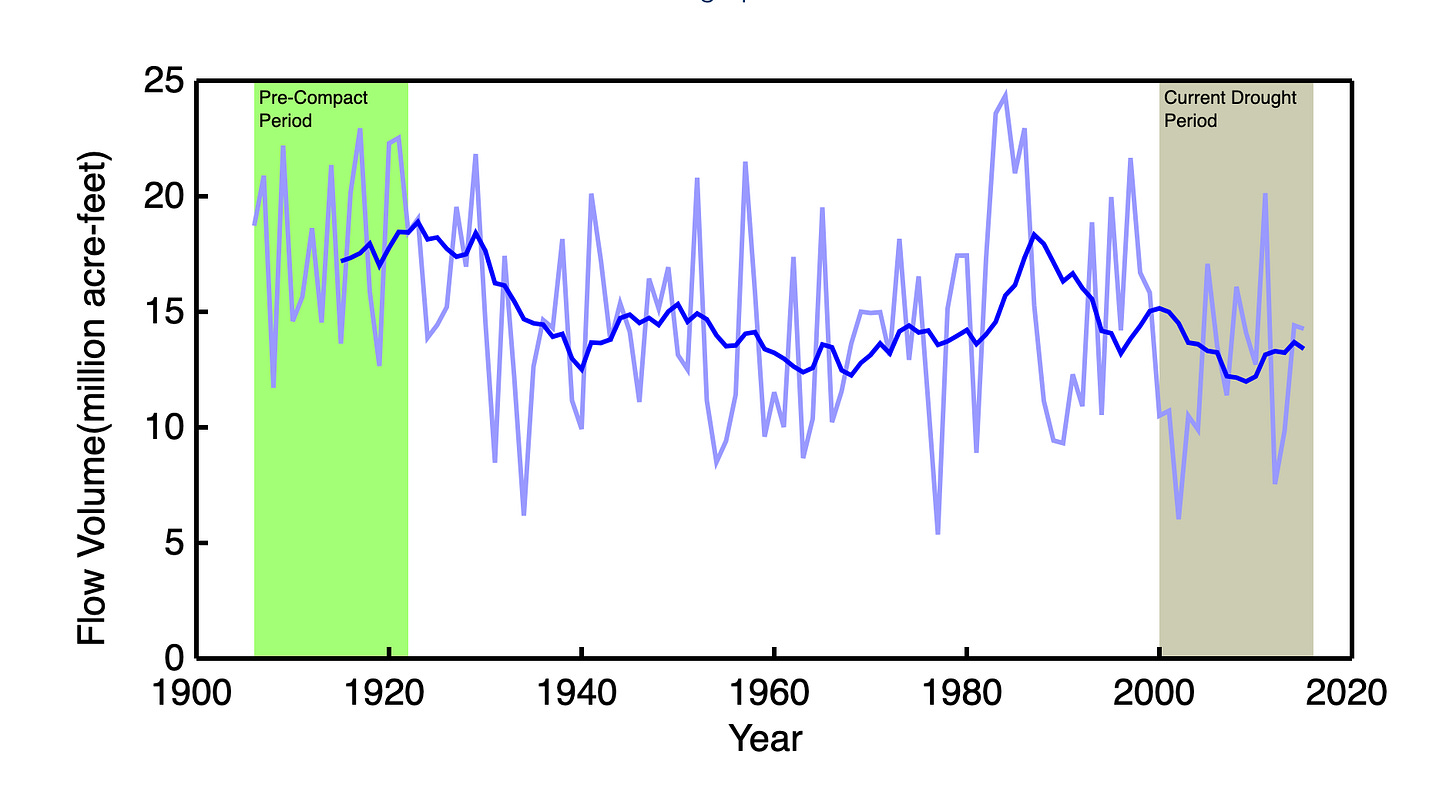

Here’s a visualization that the USGS put together. It shows the annual natural flows of the Colorado River against a 10-year running average for the last century + two extra decades. The river’s average annual flows have been at roughly 14.8 million acre-feet, but since the 21st-Century, the river’s flows have fallen steadily, bringing down the 10-year running average to far below where it was when the Colorado River Compact was signed in 1922. It’s a much smaller river. This chart ends at 2015, but things have not gotten better, and there are some great visuals in this WIREs Water paper on that. The authors report that the average between 2000 and 2023 was 12.5 million acre-feet.

Climate change has amplified the existing structural issues of overallocation, there being more paper rights to use the Colorado River than there is water to go around.

Total primary allocations contemplated in the Colorado River Compact (signed at a time of higher average flows) and a 1944 treaty with Mexico are 17.5 million acre-feet.

The math between supply and demand just doesn’t add up. That’s not exactly news.

But the challenge of dealing with it is.

How do you share the risks and realities of a smaller river? Of climate change? How do you reconcile that with key governing documents that planned for a larger river?

There is not enough water to go around to do all of the things that everyone wants (or once wanted) to do. True even before climate change, but the megadrought has put the river’s overuse in stark relief. If that’s not a new point, it’s starting to feel more real as the states are asking to put durable cuts on the table in bad water years. Now the negotiations are not only about getting by, but how to square the fundamentals.

The Lower Basin states, which draw from Lake Mead, argue they have already done much to prepare. Together, they have reduced their consumptive use about one-third in two decades, a complex, expensive and painful process that required a lot of people to brush aside hypothetical legal test cases. In a future where more cuts are needed to deal with a smaller river, they now want Upper Basin states (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming) to share cuts if the volume of storage reservoirs fall below 38%.

The states in the Lower Basin argue that the Upper Basin has motivation to do so. The Lower Basin points to the 1922 Compact, which requires the Upper Basin to deliver its full allocation over 10 years, or face a “call” or curtailment of their use.

The Upper Basin states, in the headwaters and upstream of the river’s two largest reservoirs, argue they are first to get cut as aridification, driven by climate change, leaves less water in the tributaries that feed the mainstem Colorado River. In other words, they feel the pain every year and already face de facto cuts in dry years. The Lower Basin, by having places to store their water, is shielded when they use more water than there is supply. Their proposal, as a result, requires Lower Basin states alone to take further cuts when the system’s two main reservoir’s drop below 20%.

The Upper Basin points to the 1922 Compact, which allotted it more water than it uses. And the states in the Upper Basin want to grow their water use (the Great Basin Water Network released a new map showing where these proposals are). The Upper Basin says it is complying with its obligations to deliver water to the Lower Basin.

What’s next?

The sides have been stuck here since March, and although federal officials recently outlined their own future proposals, the conference suggested the talks remain at an impasse. Maybe somewhere in between all these proposals, there is a compromise?

Conflict here is not new and it’s ever-shifting, in part because power on the Colorado River is distributed in different ways. When I first started covering the river in 2018, it was internal conflict in Arizona. Then conflict between Arizona and California. Then conflict between “senior” water users and “junior” water users. It can change quickly.

But without a deal, the alternative left to the states is testing a “compact call” to force water cuts in the Upper Basin and present the oral arguments previewed last week in court. While Arizona and California have called for analyzing a possible compact call as Arizona set aside funding for future litigation, actually going to the Supreme Court presents a major question mark for everyone. It’s a gamble, since no one is quite sure how a compact call would work, and the two divisions interpret the rules differently.

On that point, here’s a 2018 article from KUNC’s Luke Runyon outlining how a call might, sort of, work in reality. It’s notable that not too much has changed since then.

Yikes.

But maybe more to the point: Litigation could take years to resolve. And it’s not clear that water users have that kind of time amid continued overuse and climate change.

So I’ll end this with what John Entsminger, Nevada’s negotiator, said last week: “We believe compromise is possible. We think it’s the first, second and third best option.”

“But we need a dance partner. So let’s get back to the table and make this happen.”

Here’s what else I’m watching:

A trade war could bring major losses for California agriculture (L.A. Times)

Nevada climatologist brings lessons from Mount Everest (Nevada Independent)

Tribes boost Lake Mead, hope for passage of $5B water act (Nevada Current)

Farm runoff may be tied to respiratory illness near Salton Sea (Civil Eats)

Arizona water agency proposes 'ag-to-urban' plan (KJZZ)