Q&A: Groundwater loss on a global scale

ASU's Jay Famiglietti on the alarming drying of Earth's land surface.

The trend plays out in arid regions across the globe. It goes like this. Rivers dry up and water supplies become more variable. Faced with scarce surface water supplies, cities, farms, and companies look to groundwater to meet demand.

Groundwater is hidden, limited, and underappreciated. Aquifers get far less attention than rivers, lakes, and streams—the water we can see so well with our own eyes. But in arid regions, what we cannot see is as important as the water we can see.

“Groundwater is the most precious natural resource in the dry parts of the world,” said Jay Famiglietti, a Global Futures Professor at Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability. “And it is probably the least protected.”

The past century of development in the Western U.S. and arid regions across the globe has been marked by an era of intensive groundwater use, with pumping rates often far exceeding natural replenishment rates. The imbalance has diminished the volume of water stored in aquifers, leading to dry wells, land subsidence, seawater intrusion, the depletion of streamflow, ecosystem loss, and conflict within local communities.

In some cases, water pumped out of aquifers accumulated thousands of years ago and will not be replenished in our lifetimes. Despite warnings from scientists for decades — and evidence of the mounting consequences of groundwater depletion — pumping has increased in recent droughts, marked by a warming climate.

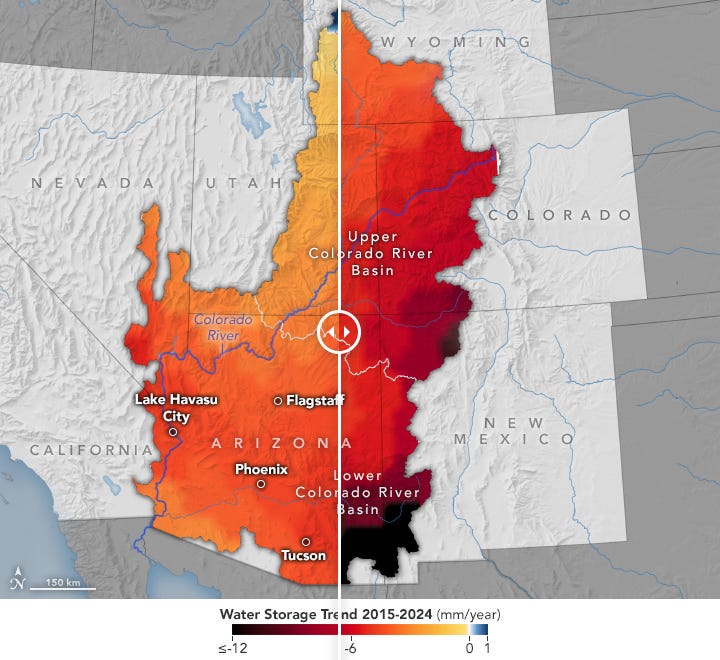

For years, Famiglietti, a former senior water scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, has worked to quantify and visualize the loss of groundwater storage using satellite data obtained through NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission. In a paper published in Science last week, his team found “unprecedented” freshwater loss across Earth’s land surface, a phenomenon they refer to as “continental drying.”

Perhaps as important as the overall trend is this finding in the paper: Groundwater loss accounted for 68% of total water lost in “non-glaciated continents.” This paper comes only two months after Famiglietti and his team published a paper showing that groundwater accounted for 71% of all terrestrial water storage lost over the past two decades in the Lower Colorado River Basin, which includes Arizona.

We spoke this week about the importance of the findings and why groundwater is so often overlooked, despite its critical role in our water supply.

What are some of the highlights of the paper, and what are you finding when it comes to groundwater’s contribution to total water storage loss? If I had to pick one thing that I want people to know, it's really about groundwater. Because everyone knows that climate change is happening. Stepping back a bit, other really important things for people to know are that the continents are losing so much more water every year than we thought, and that the rate of drying has increased, and the areas that are drying — the desertification — is increasing.

The expansion of the drying is happening because of climate change. But the response is to use more groundwater. So it's like a positive feedback. It accelerates the drying.

When you talk about global freshwater losses on Earth’s land surface, the question that many people might have is, loss to what? It’s lost to the ocean. So that’s where it accumulates. The math balances out. When we think about the globe, where do we store water? In the ocean, on land, and in the ice sheets… And, as the land storage and the ice sheet storage go down, the ocean storage goes up.

What are the broad implications of this for arid regions? In arid regions, we also see growing demands for water, not only with cities, but with agriculture and industry. Overall, in these regions, it’s no surprise they are becoming more water scarce. We’re helping quantify the rate at which they’re becoming more water scarce, and at least in a global sense, giving a rough picture of where that water is coming from.

I think the challenge for water managers is to account for this stuff… State by state, region by region, we have to decide how we are going to allocate our water. In the U.S., especially when it comes to groundwater, that’s state by state. That’s good that you don’t have Big Brother telling you what to do. But I think that’s the challenge: States are going to have to prioritize what it is they want to do. We can use Arizona as an example. Do we want to have more housing development? Do we want to have more chip manufacturers and data centers? All those things take water. Is it going to come at the expense of agriculture? What does the balance sheet look like?

What do you see historically with groundwater? Do you see this trend worsening over time? Do you see it peaking in droughts? The time scales on that question are important. The long-term is long-term groundwater depletion around the world, especially in places that grow a lot of food, or especially in arid regions. So that's the long-term trend. Sure, you get some recovery during wet periods. But then you get more groundwater use during drought. And so when you chart the long-term, you see a little bit of upward bounce during recharge periods, and then a big drop, and then a little upward. And the upward is never enough to compensate for the groundwater use during drought.

That's the trend. It's been going on since the Industrial Age, since we’ve started pumping groundwater. I think one of the challenges is that it’s tough for people to understand. It's just like with climate change. We've had something so good for so long, it’s really hard to give it up.

Why do you think it is so much harder to see groundwater? Is it simply a function of it being a subsurface resource, something we can't visualize, or is there more to why we have turned a blind eye to groundwater management for so long? I think a lot of it is because it’s invisible. And I think a lot of people, because it's invisible, don't understand it. Who knows what was taught? I never really learned about groundwater when I was in high school or anything. I know that my kids did.

I think that over the last few decades, our understanding of climate change is much greater, and our acceptance in the United States is much bigger. Our population has grown a lot, and also in that time period, you have a lot of actors, mostly industrial agriculture, that understand that they can exploit the resource legally. So while we, the rest of the world, are figuring this out, they're in there pumping away. It’s really a combination of all those things. The biggest thing, though, is that it’s invisible.

How do you conceptualize the timescale of this problem, especially when thinking about recovery times for groundwater aquifers? If a community were to develop or try to develop a groundwater management plan, and if communities start looking at how to balance the budget sheet, with all this debt accumulated over the years from over-pumping, what are the paths to move forward in a sustainable way? First, let's just address what I think is the most important question: Can we refill them? And the answer is no. You're not refilling. So then I think the next question is, how do we hang on to this as long as we can? And that takes courage. Let’s go state by state in the United States. It’s a state-governed thing. And it takes courage on the part of the state government, over successive administrations, to understand the importance and how we can conserve that water.

You talked about the governance piece, about groundwater typically being in the domain of state and local government. With some of the papers you've published recently on the Lower Colorado River Basin, and some of the other work that you've done, I’m curious if you see a need for broadening that governance to a watershed scale or to a national scale. And then how do you kind of square that with the fact that these are localized problems? The geology is localized. It varies from aquifer to aquifer, yeah. How do you view this governance piece? It's very tricky, and it's mainly tricky because of the heritage of our water law and policy, not just in the United States, but all over the world. Most of it was enacted before we really understood how the water cycle works and the connection between surface water and groundwater, and what is groundwater anyway? So I think that there's a greater need for interstate and intranational, and international cooperation on groundwater.

I think there's a need to talk about groundwater in the Colorado River Basin because of the obvious disappearance of surface water and the obvious need to use more groundwater. And then nationally, I think we need to have a better plan. And we were starting to have a better plan. We had a nice pathway there through the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. They did a lot of work on groundwater and produced the PCAST report at the end of the Biden Administration, and that rapidly disappeared on Inauguration Day.

I think the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act in California is a good model in the sense that it allows for the local control and the local understanding that we're talking about, because you have to know your aquifer. The hydrogeology is quite variable, and so there's no one-size-fits-all. Different regions will have different priorities. And by allowing that local control, you allow for different regions to come together on what their priorities are. So then why do you need the larger coverage, state or national? So at the state level, California is a great example. If your region isn't complying — or if a region isn't covered by some kind of management agency — there has to be a backstop.

I could see the same thing happening nationally. First of all, more money for monitoring. Make sure we have robust monitoring networks and data collection. All that stuff is critical. But then I can also see, at a very sort of light level, a requirement that every state has groundwater management in place, and that it's effective. Show that it's working.

Is there anything else you want to add? I think it's really important to talk about, in an era when research funding is getting major cutbacks, why something like this matters. This is fundamental to our existence. Water is life, and the things that are in this paper are critically important. It's really showing the trajectory of how our water storage is changing, and how the dry lands are expanding, ice is melting, and sea levels are rising. The things that are in that paper are so startling. We would not have known them without being able to do this research, have the satellites, and so on.

This is a practical example that comes down to your house, your neighborhood. Water is the messenger that delivers the bad news about climate change to your house. You need that information, and if you don't have that information, you're going to be in trouble.

+ Read more: ProPublica did an excellent piece on the study.

Clearing out my inbox, tabs, etc…

Minutes after I clicked publish on my last post, Western Resource Advocates released a report on policies as data centers expand into the arid West.

The West is, in fact, water scarce, despite claims to the contrary in this piece in Matt Yglesias’ Slow Boring Substack headlined “There’s plenty of water for data centers”).

’s Jonathan Thompson wrote a good rejoinder this morning, that is worth reading because “No, there is not plenty of water for data centers.”New ideas, but “old problems” surfacing on the Colorado River.

From the California Water Blog: “Relative to other western states, settled tribal water rights claims in California have been substantially smaller and had less impact on the state’s overall water allocation system. The current obstacles to tribal water rights in California are rooted in the state’s relatively early colonization and its aggressive land dispossession tactics, which ultimately diminished tribes’ water claims.”

Thanks as always for reading. You can support this newsletter by subscribing. If you can afford to support this work with a paid subscriptions, they go a long way keeping this newsletter free for others to read and sustainable to produce. I am exploring ideas to provide other member perks to paid subscribers. You can also support this newsletter by sharing it! Cheers, Daniel

Great article! This multi-level governance model has a strong parallel in Australia. To solve their crisis in the Murray-Darling Basin, they implemented a national plan but also created robust water markets. Separating water rights from land allows water to be traded to where it's needed most, whether for agriculture or environmental flows.

California's riparian water rights are insane.. Its a 19th-century concept colliding with 21st-century reality in a drought-prone state with 39 million people.

I’m a fine art photographer who has been documenting disappearing desert springs which as you know are windows into the aquifer and ground water for the last 8 years.