Hello, and welcome to Western Water Notes.

I’ve been in book world the past couple of weeks, and I came across a few old studies of the Las Vegas artesian aquifer. I tried not to go too far down the rabbit hole, but I I’ll admit that learning about the way these springs rose to the surface, and their sheer force, really struck me.

If you’ve read a few of these, by now you probably know my writing is often stuck in the past. I like old historic documents, mostly because there’s almost always a through line to the present.

Filling in the puzzle pieces of history helps me better understand how we got to today. And I’d argue that applied history matters greatly in understanding how we got to where we are today with water management in the West. Everything seems to hinge on history. This is especially true in the priority system — “first in time, first in right” — where who claimed water first has real-world consequences. Everyone wants to prove a prior right, so applied history matters.

Now, the usual housekeeping:

To get all my posts in your inbox, click the button to subscribe below. This newsletter is free, but if you find my work valuable and want to support it, please consider the monthly or yearly subscription plans below. You can also support my independent journalism by sharing these posts with friends or on social media. As always, drop me a line with feedback or suggestions.

-Daniel

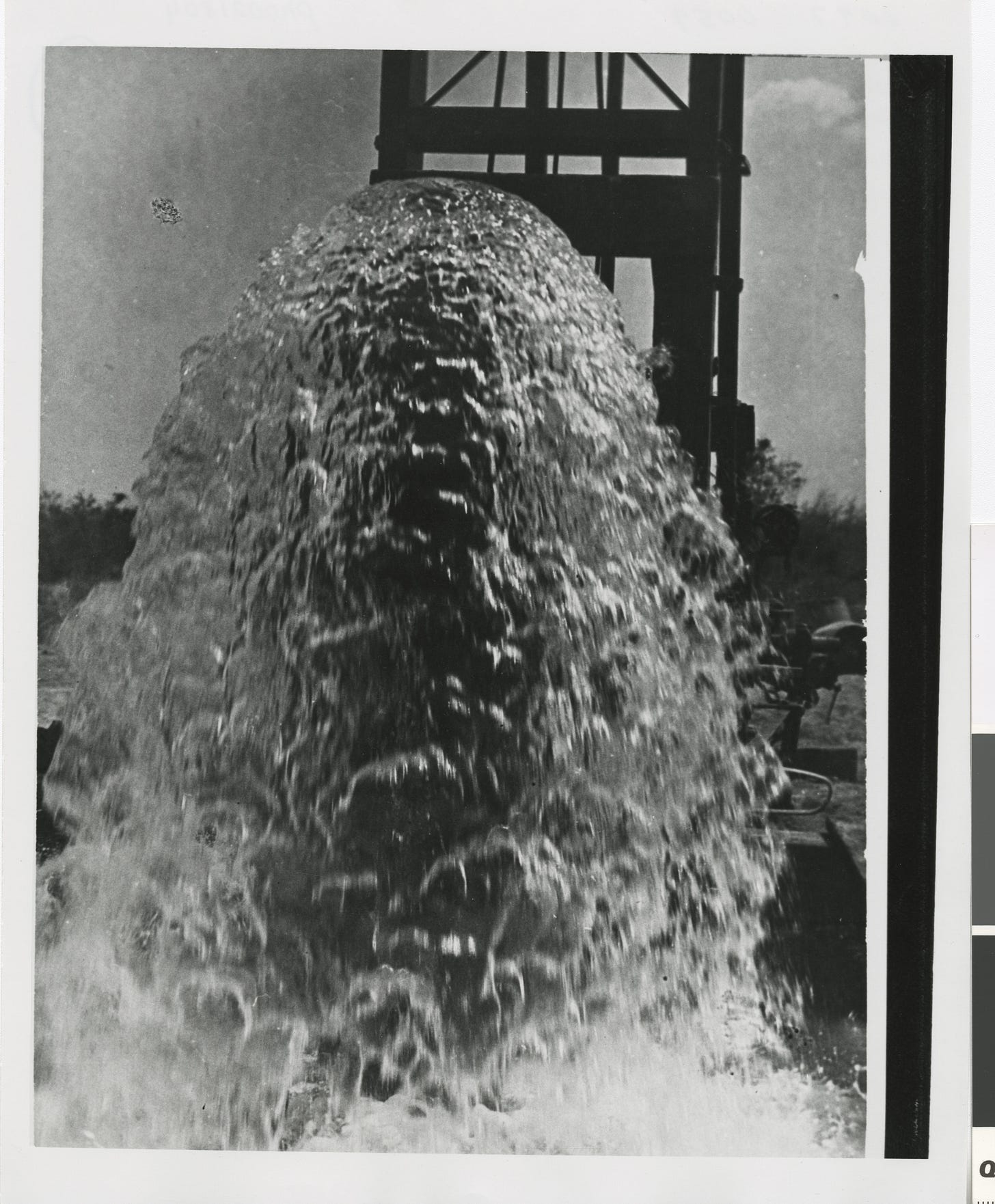

The way water used to burst from the ground in Las Vegas is hard for me to fathom — until I actually see photos of it. There is a reason they call Las Vegas “the meadows.”

Before all the concrete and master-planned communities, before traffic, red cones and cranes, Las Vegas relied on artesian wells. Because of the geology beneath the Earth’s surface, underground pressure and physics, these coveted artesian wells sprayed water into the air without pumping. In Las Vegas, such wells offered an early water supply.

These were the free-flowing and freewheeling days of Las Vegas water.

In reporting on the West and researching water, I often hear of communities that first rely on surface water, turning to groundwater decades later as an alternative to rivers and streams that have been fully divided (sometimes over-appropriated) or as a means to provide greater certainty. With its artesian aquifer, Las Vegas went the other way. It first developed its artesian aquifer long before it came to rely on the Colorado River.

Yet as the city grew, it became increasingly clear the aquifer was depletable.

After the construction of Hoover Dam, Las Vegas was expanding. An industrial sector developed during World War II and its tourism industry was growing. With the new growth, water use increased, and at a certain point, it was not only artesian wells.

A U.S. Geological Survey report published in cooperation with Nevada in March 1945, estimated 125 wells in the Las Vegas Valley in 1924, roughly 275 by 1935 and about 450 wells by 1945. Here’s a map of scattered Las Vegas wells from the 1945 USGS report:

Why were USGS and Nevada officials doing this report in the first place?

Investigations had already been underway to understand the artesian aquifer — and its limits. How much was too much groundwater use? What was a safe yield to use?

All these questions mattered because it had been clear, for years, that the Las Vegas groundwater aquifer was facing an uncertain and depleted future. Water was wasted at rates that alarmed state lawmakers enough to push legislation to prevent it. Indeed, the situation in Las Vegas paved the way, in part, for the state to pass comprehensive groundwater regulations, according to a paper by Hugh Shamberger, a former Nevada state engineer who did field work on the Las Vegas Valley aquifer early in his career:

“In the latter part of 1938, State Engineer Alfred Merritt Smith and his staff, realizing the seriousness of the underground-water situation in Las Vegas Valley, took the first step leading to the enactment of an underground water law and full-scale cooperative program with the U.S. Geological Survey, covering the Las Vegas Valley artesian basin. At that time no effort had been made by the Office of State Engineer to control free flow from a large number of wells that were wasting water because of the lack of any controlling device on the wells. It also appeared that considerable underground leakage existed from some of the wells.

…

In fact, the general belief among the population was that the underground water resources were unlimited. The author was told on a number of occasions by the manager of the Las Vegas Land and Water Company that he was convinced that the ground water had its origin in Walker Lake, 350 miles north, and that he had no concern as to the Las Vegas ground-water basin being depleted. The author, having lived in Las Vegas from 1929 to 1934 and having done survey work there, was well acquainted with the great waste of water, leaking wells, and the history of decreasing artesian pressures throughout the valley.” [Emphasis added by me.]

Groundwater, of course, was not unlimited.

In the coming years, and even then, state regulators and local officials (at least the ones who took it seriously) were right to be concern. Over-pumping of the artesian aquifer would have significant and devastating consequences. Springs dried up. Land sunk. Las Vegas faced serious land subsidence, identified by 1948 in a USGS report.

The effects of a sinking Earth are still around today. Last year, state lawmakers passed the Windsor Park Environmental Justice Act, a funding package to address the effects of land subsidence — and decades of redlining — on a North Las Vegas community.

A later USGS circular on groundwater overuse put it this way in 2008: “Since 1935, compaction of the aquifer system has caused nearly 6 feet of subsidence and led to the formation of numerous earth fissures and the reactivation of several surface faults, creating hazards and potentially harmful impacts to the environment.”

There’s a lot more to say about the Las Vegas aquifer and what regulation looked like in the years following 1945. That means more posts in the future… But for now, one of the fascinating things I took away from this research was how evident the impacts of overuse were, early on, and how they helped shape Nevada’s early groundwater law.

Unlike other states (California), Nevada created an administrative system to regulate water rights. Even so, groundwater was never easy to regulate and overuse persisted for many decades. Today, Las Vegas gets almost all its water from the Colorado River. But that wasn’t always the case, and photos of artesian wells are vivid reminders.

Some other threads

“What are baseflow droughts—and why should we care?” I found this Q&A from the Public Policy Institute of California fascinating. It looks at an important issue that’s not talked about often, exploring how groundwater interacts with surface water — and the way that it plays into long-term drought conditions.

Atmospheric rivers could get more extreme, via the L.A. Times’ Grace Toohey.

This is so true: “Saline lakes are canaries in the coal mine because they’re at the bottom of a watershed.” More in this Q&A by High Country News’ Brooke Larsen with Bonnie Baxter, director of the Great Salt Lake Institute.

Is it a beaver? No. It’s a muskrat, and they are struggling. This piece in Hakai Magazine looks at the role little-appreciated muskrat’s play in the environment and how their worlds are being reshaped, causing considerable loss: “Though their influences are subtle when compared with the wetland engineering of beavers, muskrats are still important habitat makers and nutrient movers. They help the world come to life, even if we don’t readily notice them doing so; their diminishment would reverberate far beyond them. It is also foreboding.”

I grew up in Miami before coming out West, and a formative moment for me in my water journey was seeing pictures of freshwater springs *in the middle of salt-water Biscayne Bay* that early European-American settlers used, and that of course by my childhood were gone. This post has exactly the same vibe.

link to one of the images: http://dpanther.fiu.edu/dpService/dpPurlService/purl/RM00010005/00001