Welcome to Western Water Notes.

To get all my posts in your inbox, click the button to subscribe below. This newsletter is free, but if you find my work valuable and want to support it, please consider the monthly or yearly subscription plans below. You can also support my independent journalism by sharing these posts with friends or on social media. As always, drop me a line with feedback or suggestions.

“The great plains of the state afford natural advantages for conducting water, and lands otherwise waste and valueless, become productive by artificial irrigation.” — The Nevada Supreme Court in Reno Smelting, Milling and Reduction Works vs. Stevenson (1889).

Waste. Salvage.

Two words used to talk about water over time. Two telling words.

These words jump off the pages of archival documents, reports and memos. And I’ve been thinking a lot about how they have shaped policies around water in the West.

Why write about two words? How language was used over time matters because these words shaped the laws we operate from today. To understand the system as it is today is to understand some of the motivating forces for why it was built out the way it was.

Waste

Starting with “waste.”

In writing of the “lands otherwise waste and valueless,” the Nevada Supreme Court was discussing the conditions that made the West unique and in need of a water law different from common law rules applied east of the Mississippi. It also articulated a view that arid land was in a natural state of waste but could be “reclaimed” — if only water was brought to it. This view appears often and was a consequential force behind the Desert Land Act of 1877 (still on the books) and later the Reclamation Act of 1902.

It’s present in this 1931 pamphlet, released by Los Angeles business interests, which labels a picture of the Mojave as “typical of wastelands to be crossed by Metropolitan Aqueduct enroute from the Colorado River to cities in Southern California.”

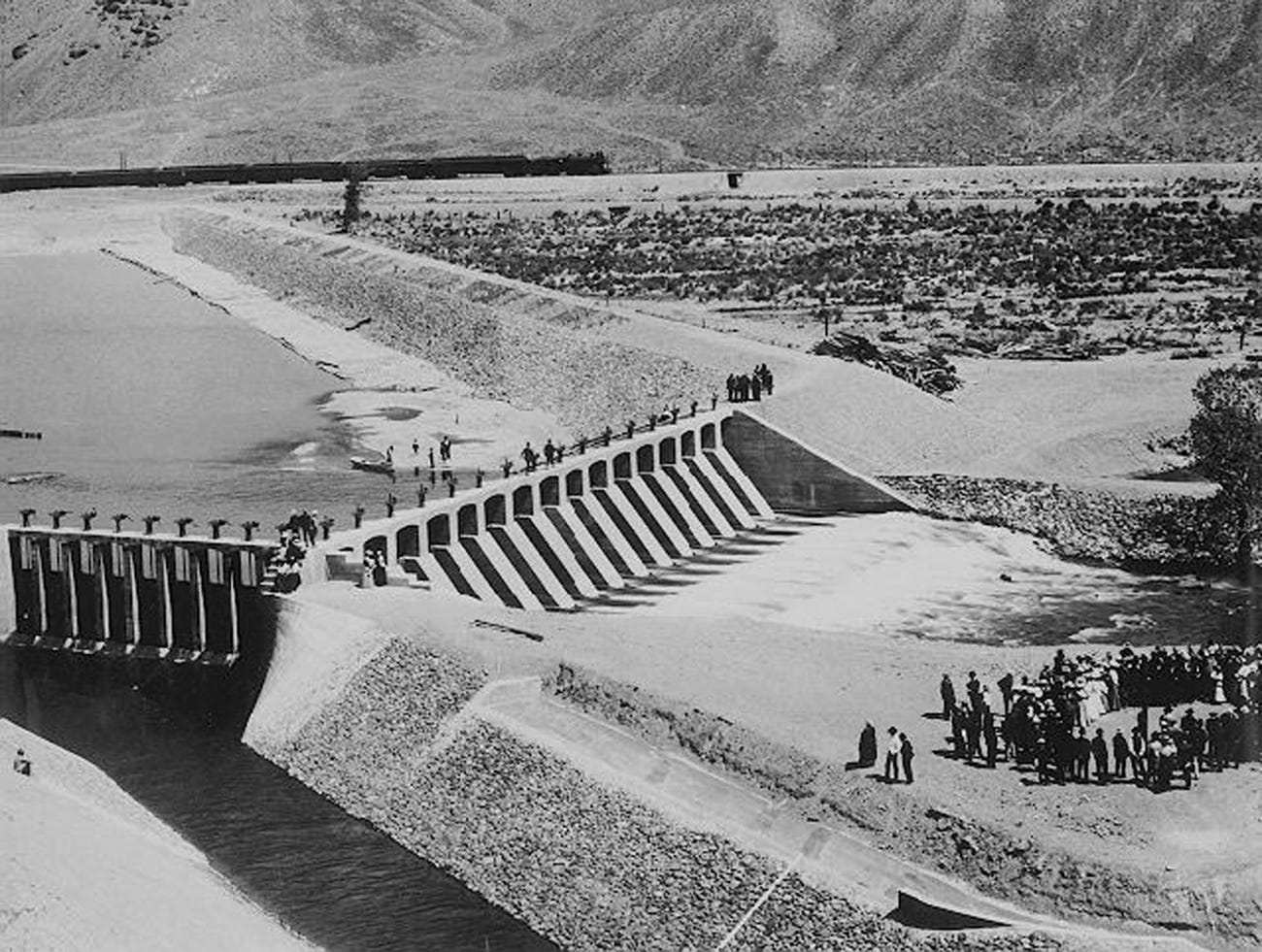

And it’s present in the dedication of the Derby Dam (pictured above) on the Truckee River downstream of Reno. The dam, part of the Newlands Project, diverted the river away from Pyramid Lake and toward arid farmland in the new city of Fallon.

Nevada Sen. Francis Newlands, of the Derby Dam’s dedication day in 1905, wrote that “the nation lifts its hand, and the waters which have formerly wasted in the sinks of the desert flow across the Divide…” The press was as glowing in its assessment with one reporter for the Nevada State Journal writing that the addresses given at the dam’s dedication event “will become history when the arid wastes teem with population.”

But what was viewed as “waste” was often far from it. When the Truckee River was diverted, the lake’s elevation fell quickly, threatening the lands of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe and two fish species, the Lahontan cutthroat trout and endemic cui-ui. The diversions further dried up Winnemucca Lake, listed as a national wildlife refuge.

Reclaiming land from “waste” could come at a steep cost. Moving water away from wet places to dry places meant wet places, in many cases, were now far drier — with consequences for the communities and ecosystems that had long relied on that water.

What was considered waste often served a “use” where it was.

Salvage

If salvage means rescue, salvaging water was rescuing it from another kind of waste.

This second word starts appearing more often with a second wave of reclamation that focused on tapping into groundwater aquifers. Groundwater may be more invisible to us but it supports springs, wetlands and vegetation in a complex, interconnected web.

Plants that tap into aquifers are known as phreatophytes. The word comes from the Greek phrear for “well.” And the name is fitting because these plants suck up water.

In the push for humans to use groundwater, policymakers targeted these plants.

The goal was to salvage the water the plants consumed and reallocate it to human use.

A 1958 U.S. Geological Survey report found, in its abstract, that “most phreatophytes have low economic value, and consequently, the water they use and return to the atmosphere without substantial benefit to man is defined as consumptive waste.”

There is the waste word again.

The report went on to say that “although little has been done so far to prevent this waste, much of the water undoubtedly can be salvaged by converting consumptive waste to consumptive use.” That is, plant uses could be salvaged for human uses.

Accordingly, this thinking formed a baseline — in some parts of the West — for how much groundwater could be used in certain places. But it was an imprecise method.

What was deemed as salvageable was not always waste. And groundwater-dependent plants could not always be so easily untethered from the water cycle they belonged to. Converting the “consumptive waste” of plants could lead to drying up groundwater-dependent springs/streams or vanishing wetlands that once had high ecological value.

Changing

Waste. Salvage.

Two words reflect a time and attitude when rivers and aquifers were viewed mostly as systems to plumb. When water not consumed for human needs was otherwise wasted.

This view, at once, fueled growth and development of the Western U.S. for decades. And it also had dramatic consequences for communities, wildlife and ecosystems — all of which remain in the present. But while the ideas evoked by reclaiming “waste” and “salvaging” water remain embedded in various laws, the way we look at water has changed — with recognition that the public interest extends beyond maximizing use.

What is and is not considered waste has changed in time. State laws now consider in-stream environmental flows and wildlife habitat to be “uses” of water, even if they do not explicitly support human consumption. And courts have attempted to balance the public trust doctrine — the concept that governments must manage water in trust for recreation and the environment — with the appropriation of water for economic uses.

Still, understanding what is and is not “waste” continues to lurk in the background.

More to come, as always.

Until next time,

Daniel

Tribal resources (water, wildlife-fish, timber, others) have been relocated and colonized beginning with Christopher Columbus!