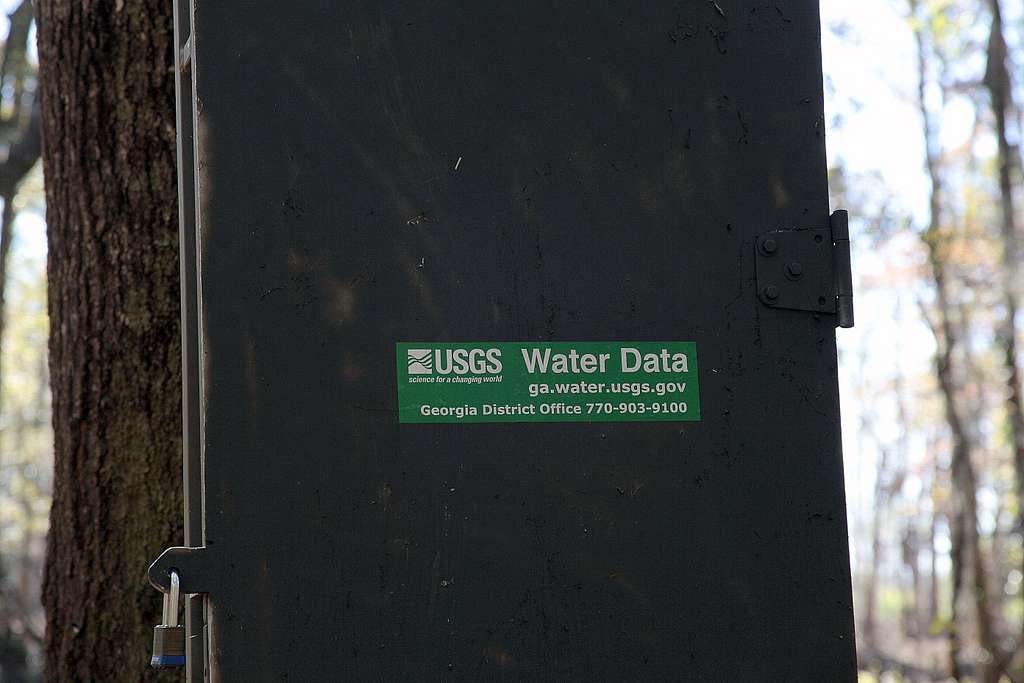

“After Meta broke ground on a $750 million data center on the edge of Newton County, Ga., the water taps in Beverly and Jeff Morris’s home went dry.” — The New York Times, 7/14

Data centers, the physical nodes of our digital economy, are thirsty.

Increasingly, this fact has entered the mainstream, as more and more data centers are expanding, stressing water supply even in places where we do not often think of water quantity as the primary constraint to growth. The New York Times last week chronicled a recent case of this in Georgia. It’s worth reading.

One quote I found especially revealing came from the executive director of the local water and sewage district. He said: “What the data centers don’t understand is that they’re taking up the community wealth. We just don’t have the water.”

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about AI over the past year. The way AI is changing an information ecosystem (past and present) that is critical to understanding how we got to where we are today, and why systems function the way they do. And, of course, the way data centers are shaping how communities allocate energy and water.

External knowledge generation and data storage, through time, has always required material inputs, whether stone and clay, wood and ink, magnetic tape and optical discs. But the volume that is stored, remotely, now is staggering. A white paper from IDC and Seagate talked about approaching 175 zettabytes by 2025. If it was all stored on Blu-ray discs and stacked up, the pile would reach the moon 23 times.

To store so much data on such a significant scale requires raw natural resources—in the form of energy and water. Generative AI queries have amplified the computing work, requiring more data centers, and accordingly, more energy and water. But we, the user, do not always see the inputs. They are still real, and they are especially real for the communities where data centers are being built.

Tech companies are building data centers across the country, and local governments are grappling with what that means. When big projects come to town, they frequently demand large amounts of energy and water, needed to cool their servers. Here is the alarming part.

As Stanford University’s Newsha Ajami notes in the New York Times story, “water is an afterthought” for tech companies who seem to have put a lot more thought into siting data centers where energy is cheap. That’s scary because water management is so context-specific. Not all surface water sources are the same, nor is the geological composition of groundwater aquifers. Water requires doing your homework, and even then, there is often a degree of uncertainty about future water supplies that hinge on climate.

If water is an afterthought, who is ensuring that it makes sense for communities to commit so much water to one or two companies? You may think it’s city officials, but municipal governments face a lot of political pressure to quickly approve data centers as they proliferate faster than there are local rules to govern them.

Significantly, data centers are straining water supplies even outside the arid West, and affecting long-term water planning. In Iowa, some of the state’s 104 data centers are mining stores of ancient groundwater that once extracted, will not be replenished in our lifetimes, according to a Harvest Public Media story.

But the impacts of the data center boom could be especially pronounced in dry areas where water is already scarce and overcommitted. Many tech companies are locating data centers in some of the hottest, most arid parts of the country and the world. I’m not sure we’ve fully grappled with what it means for future municipal water demand.

In Tucson, Ariz., right now, city officials are weighing the approval of a $1.2 billion data center project. “Project Blue,” as it’s known, would use more water than four golf courses and become the city’s largest power user, the Tucson Sentinel reported. A piece by Arizona Luminaria recently revealed that this is for Amazon Web Services. How the city will supply that water is a pivotal question. And it’s the right question to ask.

There is concern that reclaimed water to meet demand for the data centers could be taken out of the Santa Cruz River, whose flows support wildlife and important habitat. An official for the city of Tucson has pushed back on those claims, arguing that the project is “water positive.” The Arizona Daily Star has more on it.

Expect these types of issues to get louder and louder. In Nevada, as MIT Technology Review reported, state energy filings suggest that data center projects outside Reno could require billions of gallons of water per year. Some demand will be met through a pipeline delivering recycled water, but it is valid to ask about capacity over time.

The build-out of a dense cluster of energy and water-hungry data centers in a small stretch of the nation’s driest state, where climate change is driving up temperatures faster than anywhere else in the country, has begun to raise alarms among water experts, environmental groups, and residents.

There is a challenging tradeoff here, too, even for data centers that use water more efficiently. A data center’s water footprint is not all about the direct use of water.

Some data centers use significantly less water, but that reduction is often offset by increased energy consumption. Data centers are already expected to drive up energy demand so significantly in the coming years that utilities are moving away from their net-zero greenhouse gas emission pledges and back toward fossil fuels, including coal. These energy sources, especially thermoelectric plants, demand water for cooling.

The build-out of more fossil fuel plants—to serve data center demand—plays into an awful feedback loop, as more heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions further worsen the impacts of climate change, which is already worsening droughts and affecting water availability.

Data centers are coming. The consequences are real. We need to talk about them.

A few other things:

More on the Colorado River post: Recommend reading this post from Land Desk on what the new Colorado River flows framework might mean for the Grand Canyon.

Why access to running water is a luxury in wealthy US cities. (Bloomberg)

An interesting story in the New York Times about the Public Trust Doctrine, climate change, sea walls, and our changing shorelines across the world.

The Nevada Independent looks at efforts to protect the tui chub fish in Esmeralda County, and what an Endangered Species Act listing could mean for local irrigators.

As always, thank you for reading. You can help support this newsletter by passing it along to anyone who might be interested or liking it on the Substack app if you liked the post… More likes lets Substack know to recommend this to more people. Stay safe and well, Daniel

Thank you for digging into these water issues. In our small California town, Cambria, we struggle even to provide water to our limited residents, but under constant pressure to grow. The multi-million-dollar water treatment facility built in 2014 still lacks even a complete permit application to operate.

Thank you for this important story