The threat of sea level rise to groundwater

A new study looks at what's in store by the end of the century.

Hello, and welcome to Western Water Notes.

A couple of weeks ago, I talked with a JPL/NASA researcher about a new study looking at the impacts of sea level rise on coastal groundwater aquifers. Seawater intrusion is already a big problem, due in large part to the over-extraction of groundwater. But like so many things, the effects of climate change are poised to make the issue even worse. That and more (including an update on some of the latest water news) in the newsletter this week.

To get all my posts in your inbox, click the button to subscribe below. This newsletter is free, but if you find my work valuable and want to support it, please consider a monthly or yearly subscription plan. You can also support my writing by sharing these posts with friends or on social media. As always, drop me a line with feedback, ideas for posts, and suggestions.

If you read this newsletter regularly, you know my interest in groundwater stems, in part, from the fact that groundwater is invisible to us much of the time. Over the past couple years, I’ve wanted to learn more about how climate change is affecting what goes into aquifers (recharge) and what goes out (discharge).

That’s why a new study funded by NASA and the U.S. Department of Defense caught my eye at the end of last year. The study finds that, by 2100, as sea levels rise, many coastal aquifers globally are at risk of saltwater contamination.

Seawater intrusion is not a new issue for many coastal communities.

Coastal aquifers adjacent to the ocean store freshwater that is replenished, over time, from precipitation. This groundwater buffers against the seawater pushing toward it from the other direction. That balance keeps freshwater usable for drinking water and agriculture. But that dynamic starts to change with climate change as) sea levels rise and as 2) less freshwater is around to replenish groundwater aquifers in many places.

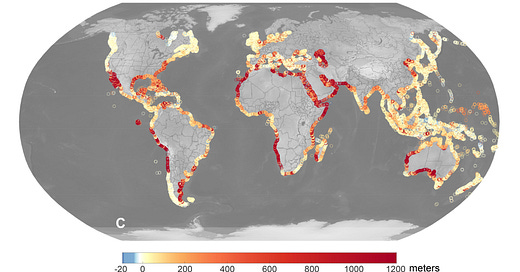

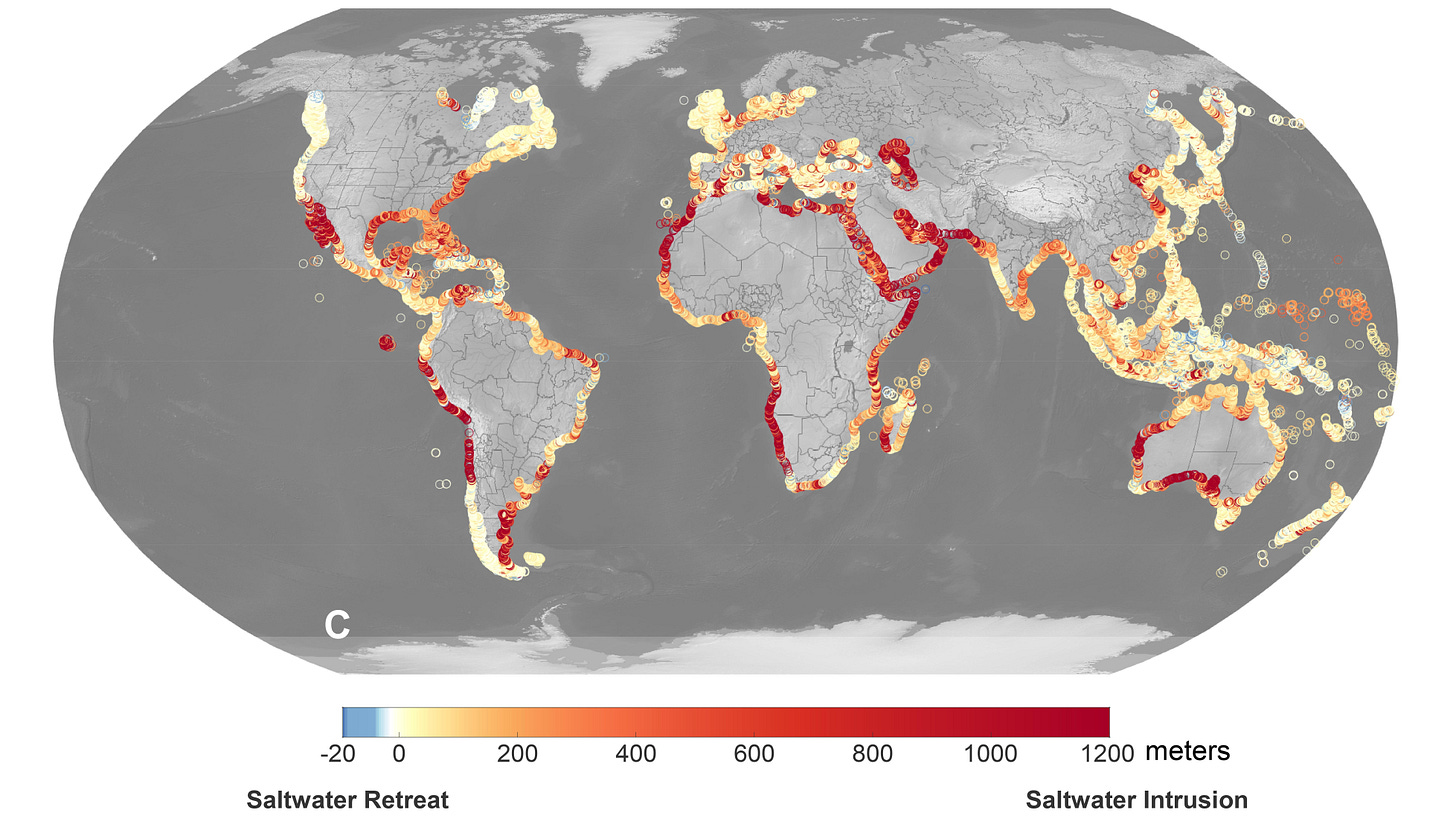

In the NASA-JPL study published in Geological Research Letters last year, scientists looked at both variables over more than 60,000 coastal watersheds across the globe.

What they found: About 77% of coastal aquifers will see salinization by 2100.

Earlier this month, I spoke to one of the lead authors, Kyra Adams, about the findings, how the study came to be and how to think about some of the results. Some takeaways:

Where ocean meets the land: The top-line result — that as sea level rises, we’ll see more salinization — was not all that surprising, Adams told me. But the study offers a glimpse into how the severity of seawater intrusion hinges on what happens inland.

In dry places, you could start to see the “heavy hitters.” Less precipitation could mean less water replenishing aquifers, creating a large void that rising seawater could fill.

The result: Vital underground freshwater supplies are contaminated with seawater.

Then add groundwater pumping: The study looks at climate change projections, but it leaves out some human influences that could make matters worse. “There are a lot of complex things at play, but what we really wanted to focus on for this work was the two large climate variables without any of the anthropogenic effects,” Adams said.

“You could think of our work as kind of the worst-case scenario baseline,” she added.

When cities or farms pump too much groundwater from basins on the coast, it can create a void for seawater to infiltrate. Couple that with rising sea levels and changes to the water cycle, and you can face serious risks for a contaminated water supply.

An infrastructure problem: Salinization matters not only for water use, but for civil infrastructure, Adams noted. “You can imagine salinization at depth. Although it is slow moving, silent and maybe doesn’t show as much oof visible effects as overland flooding, it could corrode pipes and it can really damage building foundations.”

“You build a system thinking it’s going to be a fresh system, but if you introduce salinity, it’s not going to be great. Same for things like marshes and wetlands.”

What it means for management: The study provides a broad look at the issue — a snapshot at a regional and global scale. But by looking at the combined risks of both reduced recharge and rising sea levels, it might offer communities some insight into what could be the main driver of salinization, Adams said, cautioning that localized and regional analyses are needed to account for specific geologies and contexts.

“I think kind of a binary classification can be done,” Adams added. “Do we need to focus on really guarding what we have for groundwater and recharge? Or do we need to understand which sea level rise scenario we are tracking at the moment?

In other news:

Going to write more on this general subject at some point (because we focus so much on water supply + climate change and probably not enough on demand)… but the Las Vegas Review-Journal reports that Southern Nevada saw its Colorado River use tick up last year. The article headline says soar and that seems a little much (water use was still lower than in years past). But since the increase is attributable to heat/aridity, it speaks to the way that warmer temperatures affect not only water supply but demand.

The Bureau of Reclamation released an alternatives report for the Colorado River.

Rain is finally coming to Southern California.

There’s a lot to say about the Trump administration (see the executive order issued on Monday), California water and the Delta. I will inevitably be writing more about this too. But for now, I wanted to flag some really good pieces on what this is all about:

KQED’s Ezra David Romero on the misinformation and the political realities.

More from CalMatters on the political reality with quotes from those involved.

Speaking of water demand, the new administration is also pledging to ease appliance efficiency standards, a driver of water use reductions in urban contexts over the past several decades and lower utility bills for many consumers. More from the AP.

A final newsletter note

I know a lot of news is rightly focused on the federal government and the firehose of executive actions coming out of the new administration. I am watching too. And while this news is vital, I still think it’s really important to tell stories about our world beyond national politics. That’s how I see the function of this newsletter. Physics stops for no one and at a no time.

And the physical realities on the ground will always catch up to us in the end. Better that we pay attention and plan with good information. That said, please let me know what you think and if you have any feedback or suggestions about my approach to covering these topics.

Until next time,

Daniel