Hello, and welcome to Western Water Notes.

To get all my posts in your inbox, click the button to subscribe below. This newsletter is free, but if you find my work valuable and want to support it, please consider the monthly or yearly subscription plans. You can also support my independent writing by sharing these posts with friends or on social media. Or you can contribute a tip through the Buy Me a Coffee platform.

As always, drop me a line with feedback or suggestions.

Groundwater supplies are disappearing. For decades, states and local communities, especially in the Western U.S., have been grappling with the consequences of pulling water out from aquifers at a far faster rate than water replenishes them. The result is a deficit that has widespread geological, economic, social, and ecological ramifications.

But the issue of groundwater depletion gets far less attention than the water shortages we can see with our own eyes — streams running dry, reservoirs crashing to dead pool.

That’s starting to change. Overdraft is getting some national attention.

In December, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology released a report recommending the federal government take a more active role in managing and understanding groundwater. The report also highlights what is at stake. Nearly half of U.S. drinking water comes from the subsurface. Aquifers feed streams, springs, and wetlands. Groundwater is tapped for irrigation, construction, and mining.

“The U.S. is facing a serious and unprecedented groundwater challenge,” the council wrote in a letter. “In many aquifers, groundwater withdrawal has outpaced natural recharge, which is exacerbated by the changing climate and precipitation variability.”

The report’s recommendations are not prescriptive. That is, the report does not say how groundwater should be managed. Nor does it offer a one-size-fits-all solution.

In fact, the authors recognize an important reality that “groundwater governance in the United States is characterized by a highly decentralized framework, wherein each state is primarily responsible for creating and enforcing its own laws, policies, and regulations.” This governance system, they authors write, is both “appropriate and inevitable in the case of groundwater, because of the level of physical (geologic, ecologic, and climatological), economic, and political heterogeneity among aquifers.”

Instead, the report advocates for the federal government to play a role in research, data and modeling groundwater to better evaluate supplies. It also encourages more federal incentives to replenish depleted groundwater aquifers. A few examples:

Recommendation 1. Accelerate the development of a comprehensive repository for data and toolkits for groundwater storage, withdrawal, and recharge at spatial and temporal scales useful for water managers and users.

Recommendation 2. Establish a research program to advance technologies and strategies for safeguarding the future of groundwater supply and quality.

Recommendation 3. Establish a federal incentive program and a network of groundwater engagement hubs, including Tribal Nations groundwater engagement hubs, to support and assist in planning sustainable groundwater use.

Recommendation 4. Create a competitive grants program to incentivize the planning, sustainable management, and restoration of aquifers, along with the surface waters critical to their recharge and cleanliness.

It’s notable that the federal government could get more involved with groundwater.

As the report acknowledges, groundwater in the West is typically governed by states and local communities. The federal government takes a hands-off approach. Such a system provides a lot of flexibility, but it also creates gaps in management between states. Some states (like Nevada and Utah) have had permit systems for groundwater going back decades. Other states (Arizona and California) were later to regulating it.

Still, this would not be the first time the federal government is getting involved in characterizing and managing groundwater in the West. The U.S. Geological Service has long worked to create estimates of groundwater recharge and discharge across the West, and more recently remote sensing from NASA has helped fill in water data gaps.

In the early part of 20th Century, ahead of a groundwater boom driven in part by rural electrification, technological advances and the need for new water supplies, the USGS expanded its workforce to study groundwater from about four hydrogeologists in 1911 to about 81 in 1941, according to a history of the time. Their jobs were to not only to identify where groundwater was available but also the constraints on developing it.

The history, written by a geologist at the agency, claims that “by 1940, the Division of Ground Water [at the USGS] and the closely coordinated Division of Quality of Water made up the largest and most able hydrogeological corps in the world.”

Perhaps a similar investment is needed today.

It’s also worth noting: While the Western U.S. is a hotspot of groundwater depletion, but it is by no means alone. The decline in groundwater supplies is a global issue.

More on the White House’s effort in the L.A. Times and InsideClimateNews.

Here’s what else I’m reading:

A chance to keep tidal marsh ahead of sea rise in the Bay (Maven’s Notebook)

To solve climate change, we need to restore our Sponge Planet (Nature Water)

In Idaho, a clash over water quality and national security (Circle of Blue)

Can new sprinklers save the Colorado River? (KUER)

The year in water news: Preparing for New Mexico’s drier future (KUNM)

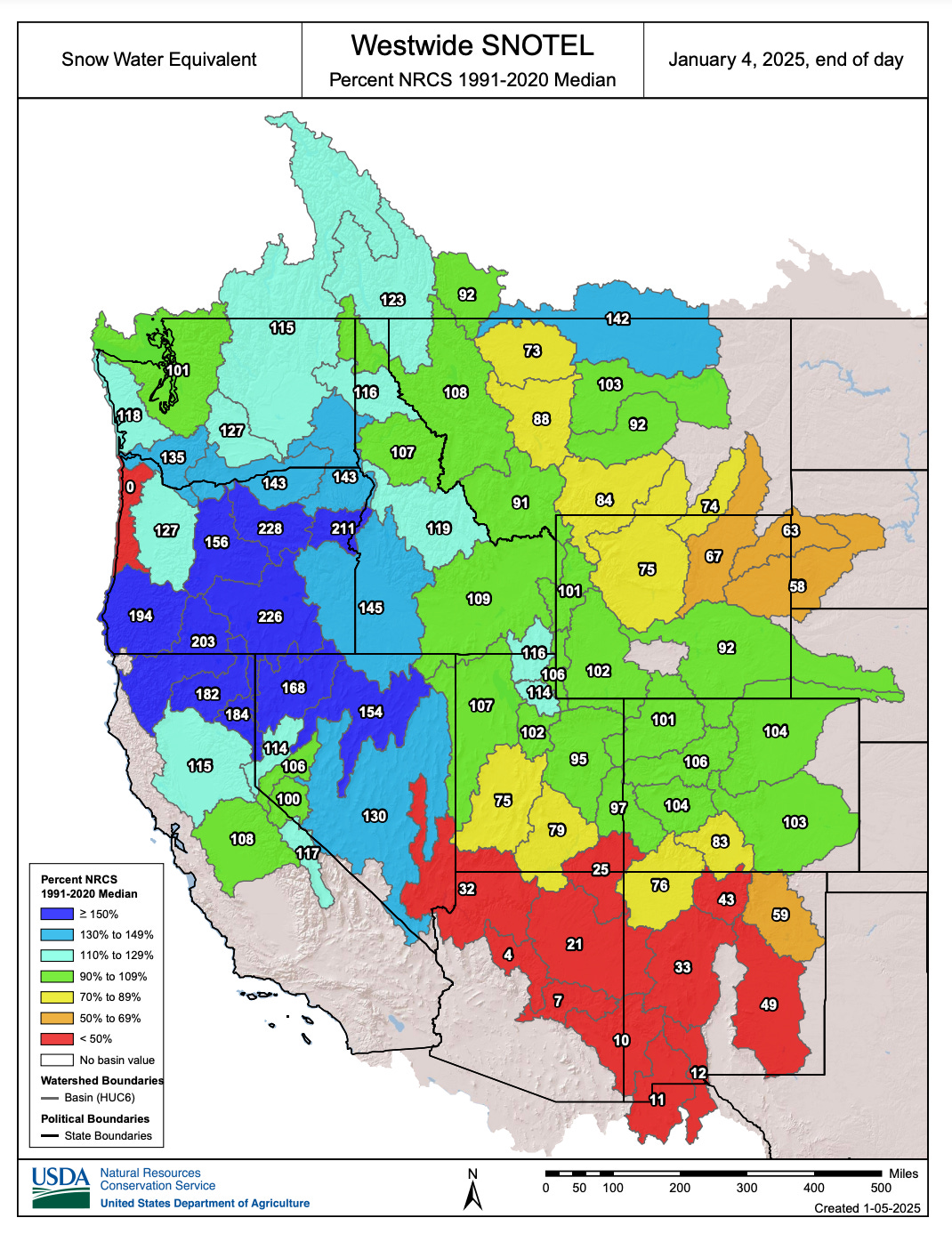

Where the snow is:

Jan. 2 marked the first snow survey for California and officials feel ‘OK.’

It’s early on, but here’s the snowpack looks like across the West right now: